Assessing the Quality of Stock Market Indices

Assessing the Quality of Stock Market Indices: Requirements for Asset Allocation and Performance Measurement

For the vast majority of European institutional investors, constructing a benchmark and measuring the performance of their portfolio in relation to the benchmark are central to their investment process. And, very often, the chosen benchmark is a market index and/or a combination of market indices.

Since their design is not affected by the securities chosen by managers and since they benefit from the sound reputation of major financial institutions, credit rating agencies and major international stock exchanges, market indices appear to be the ultimate reference not only for strategic allocation but also as a measure of investment management performance. Evaluating the quality of these indices as a benchmark is therefore a question that is essential to institutional investors.

The use of capitalisation-weighted indices is often justified by the central conclusion of modern portfolio theory — that the optimal investment strategy for any investor is to hold the market portfolio, the capitalisation-weighted portfolio of all assets. It should however be noted that empirical tests conclude that market indices are not efficient. This can be explained by the fact that these indices do not include all assets or by the fact that the theory does not hold. The practical conclusion is that using capitalisation-weighted portfolios is not necessarily the optimal method.

For purposes of asset allocation and performance measurement, the assumption of index efficiency is a central one. In addition, investors typically perceive the index to be a neutral choice of long-term risk factor exposure. These requirements mean that the existing indices may be of good or bad quality depending on the degree to which they fulfill the requirements. This survey addresses this issue using a number of well-known stock market indices.

Lack of Stable Risk Exposure

We conduct an empirical study assessing the stability of the allocations of existing indices. The goal is to identify the evolution of the weights in a range of broad market indices. We conduct this analysis since investors are typically interested in the allocation over the different subcategories of their equity portfolio. The most relevant subcategories for equity investors are investment styles such as growth and value and industry sectors. This stems from the fact that size (large cap, small cap, etc) and style (growth, value) have been shown to explain a significant portion of the cross-sectional difference in expected stock returns. Likewise, sectors of the industry are useful building blocks for constructing equity portfolios, as different sectors of the economy have different exposure to the business cycle. As the portfolio composition by style and by sector directly impacts the risk and return properties of the portfolio, this decision requires major attention from investors.

Our analysis is motivated by the fact that the index is often viewed as a somewhat neutral investment decision. However, the choice of an index as an investment support involves an implicit rather than an explicit choice of allocation. Our focus is on qualifying the type of style-/sector- allocation choices made by investing in an index. We test the stability of existing indices in terms of exposure to both investment styles and industry sectors and we find that the relative weight of the different subindices varies drastically over time.

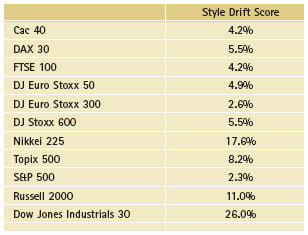

To summarise how the style weights of broad market indices vary over time, we calculate the style drift score. This score indicates the average variability of the style or sector weights for each index.

Results for the style weights are indicated in Illustrations 4 ,5, 6 and 7 of the full document. The figures show the variability of the weights given in the left hand side graphs of illustrations 4 ,5, 6 and 7 of the full study. The style drift indicator is calculated according to the method of Idzorek and Bertsch described in the complete text.

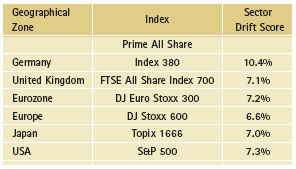

The sector weights of the market indices that we analyse also show drastic variation over time. While this may be expected, given that our period covers the technology bubble and its burst, even when looking at relatively calm periods on the stock market, the variations in sector weights are considerable. The following table shows the sector drift scores, calculated in a manner analogous to the style drift scores.

Based on the sector capitalisation weights shown in Illustrations 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13 of the full document. These sector weights are based on the capitalisations for the period of October 1995 to September 2005. The style drift indicator is calculated according to the method of Idzorek and Bertsch described in the complete text.

The variation of the weights of the sectors in the global market index leads to a problem for the investor. The sector instability emphasises the fact that the sector allocation becomes an implicit decision investor. We show that this implicit choice corresponds to a “view” on the returns of the different sectors, and we argue that holding the global market index is not optimal for an investor, unless he/she happens to share these views implied by the market capitalisation weights of different industry sectors.

If we consider each market index as a global portfolio, we can conclude on the implicit views of the representative investor. We use the Black-Litterman asset allocation model to extract these views from the index weights. We show that variations in the relative market capitalisation weights of the sectors correspond to a modification in the expected returns on the respective sector. In fact, the view of the market on the returns of the different sectors may show considerable variation. Thus, the burst of the technology bubble and the corresponding decrease of the weight of the information technology sector corresponds to a change in view of 17.40% return to 13.7% for the Euro Stoxx 300 index. Such variations may not be surprising, given that capitalisation weighting implies a trend following strategy. As a sector’s relative price rises, so too does its weight in the portfolio. Implicitly, rising prices lead to an expectation of higher returns. Investing in the index means accepting these views, which may seem counterintuitive.

Lack of Efficiency

As stated above, we examine the efficiency of existing stock market indices since efficiency is the major claim made by index providers to establish that capitalisation weighted indices are a good investment choice.

We test the distance in terms of efficiency between a market index and its alternatives. These alternatives are based on portfolios of individual stocks rather than portfolios of style indices or sector indices in order to avoid a bias linked to a different universe of assets for the style/sector versus the market index. The question as to the efficiency of the index is whether an investor may obtain better results by using the same universe of stocks but a weighting scheme that is different from capitalisation weighting. We assess two weighting schemes — mean-variance optimisation and equal weighting.

Our conclusion is that the existing stock market indices are highly inefficient compared to the mean variance optimal portfolios. We show that the indices lie below the efficient frontier. Interestingly, even a simple weighting method such as equal weighting of the component stocks leads to more efficient portfolios than the capitalisation-weighted indices.

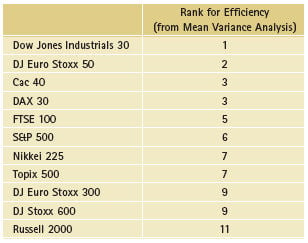

We can summarise the results obtained for existing stock market indices by showing their rank in terms of efficiency. This result is shown in the following table.

The poor efficiency score of capitalisation-weighted indices may not be surprising, given that the weighting method automatically gives very high weights to some components and leads to concentrated portfolios. Usually, the 10-30 largest stocks make up the majority of the weighting in the index. Put differently, even if an index has more than 500 components, 90% of the components make up an almost negligible part of the index weights. Also, as shown by the dramatic changes of sector weights, at certain stages, some sectors have a dominant weight in the index.

It is interesting to note that the index that performs best is the only index that is not capitalisation-weighted. The Dow Jones Industrials Average actually uses a price-weighting methodology. While this methodology is subject to severe criticism, it seems that capitalisation-weighting is even less attractive in terms of efficiency.

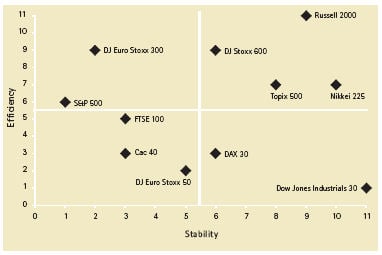

The illustration below maps the indices according to their ranks for the style stability and the efficiency criterion. This illustration shows visually what the profile of each index is. The indices in the “south-westerly” quarter of the graph have high ranks in terms of both efficiency and stability. The indices in the “north-westerly” quarter have low ranks for efficiency, but are in the upper half of the indices studied in terms of the style stability criterion. Likewise, the indices in the “south-easterly” quarter are poor in terms of stability of style, but are among the most efficient. Finally, the “north-easterly” quarter contains indices that have low ranks according to both criteria

This illustration is based on Table 20 of the complete document. The rank obtained for the efficiency criterion is indicated on the vertical axis while the rank obtained for style stability is indicated on the horizontal axis. The lines at the centre indicate a rank of 5.5, which corresponds to the average rank among the 11 indices. The ranks are based on Table 7 (section two) and Table 15 B (section three of the complete document). The indices are ranked in ascending order for the style drift scores from Table 7. The ranks for efficiency are taken directly from Table 15 B of the complete document.

This illustration shows quite clearly that there is no index which unambiguously dominates the other indices. The S&P 500, for example, has the lowest style drift score from style weights that were obtained from a returns-based style analysis. On the other hand, when the location of the S&P 500 index in the mean variance plane is compared to portfolios on the mean variance frontier, it only obtains the sixth rank among all the indices studied. Likewise, the Dow Jones Industrial index obtains the leading rank in terms of efficiency, but shows pronounced variability of style weights leading to rank 11, the last rank among all the indices, with respect to this latter criterion.

It should be noted that indices for the same geographic regions obtain quite dissimilar profiles in this plot. For the US stock market, for example, the S&P 500 ranks well in terms of style stability and poorly in terms of efficiency, the Dow Jones Industrial ranks well in terms of efficiency but very poorly in terms of stable style exposure. The Russell 2000 index obtains low ranks with respect to both criteria. The picture for European and indices is equally disparate, while the Japanese indices map each other more closely.

Indices that rank well, both in terms of stability and efficiency, are the CAC 40, the FTSE 100 and the DJ Stoxx 50. These indices rank in the upper half of ranked indices according to both criteria. The most attractive one seems to be the CAC 40, which ranks third in terms of both criteria.

Implications and Remedies

In the last section of the study, we show some implications of the results from the empirical sections for different stages of the investment process, namely asset allocation and performance measurement. Should it be said that commercial indices are sub-optimal investment vehicles that should simply be avoided by investors? We actually believe not, as there is evidence that commercial indices can be used as building blocks to design efficient allocation strategies.

In order to deal with the problem of an exposure to risk factors that vary over time, we propose to build completeness portfolios that neutralise the sector biases of an index.

An obvious way to deal with the lack of stability is to construct portfolios that have constant weights over time. However, if investors choose to construct a portfolio themselves, they will forego some of the implementational advantages of investing into broad stock market indices (such as low management fees, low transaction costs, low information costs and simple implementation of orders dealing with intermediate cash flows). Therefore, we propose to construct completeness portfolios that allow for an investment in broad stock market indices while neutralising the sector shifts inherent in the indices. We concentrate on sector biases (rather than style biases) since sector weights are directly observable using the market capitalisation of sectors. The analysis is done for all portfolios where we did the sector stability analysis above, using the same dataset.

Adding the completeness portfolio resolves the problem of investors not being in control of the sector exposures of their equity portfolio. In addition, investors hold portfolios whose weights remain fixed, unlike with a buy-and-hold strategy.

These completeness portfolios not only have more stable sector exposure, but also achieve more favourable performance in terms of risk and return. Thus, investors seeking the most attractive risk return profile for their portfolio could benefit from implementing a simple neutralisation strategy by holding a global index and a completeness portfolio made up of sector indices. Similarly, for purposes of performance measurement, investors can construct benchmarks that are more sophisticated than a global index, by choosing a combination of indices. Such a benchmark is often called a “customised benchmark”, to emphasise the fact that it is not simply a global index.

The fact that global indices show a pronounced lack of efficiency is probably the most interesting result of this study. The remedy we proposed for the asset allocation phases of the investment process is to construct efficient portfolios, for example from sector indices. These sector indices can be used as building blocks in an optimisation procedure that makes it possible to avoid the drawbacks of the global indices. The approach we proposed avoids estimation risk by focusing on the minimum risk portfolio and shows significant enhancement of efficiency in an out-of-sample exercise.

Our results show that the volatility of the minimum-variance portfolio is always significantly lower than that of the corresponding market index. It is important to note that this dominance is not achieved by construction and the portfolios can actually be obtained ex ante by an investor.

It is striking that the lower risk of the minimum-variance portfolio does not lead to a lower expected return for five out of six indices. This is only the case for the minimum-variance portfolio of sectors that make up the S&P 500 index. All other minimum-variance portfolios also have higher expected returns than the corresponding index. Consequently, the Sharpe ratios show strong improvements compared to the market index, except for the S&P 500.

On the Usefulness of Equity Indices

While our findings show that commercial indices pose serious challenges for an investor who wishes to use them in the investment process, these drawbacks do not necessarily mean that an investor should not use indices at all. Quite to the contrary, we have shown that there are straightforward remedies for the problems of commercial stock market indices.

We have looked at such solutions for both asset allocation and performance measurement.

To conclude, it can be stated that this study identifies numerous problems with commercial stock market indices. At the same time, we propose a number of pragmatic solutions to these problems. All of these solutions are based on indices that reflect finer sub-segments of the equity market, such as investment styles or industry sectors. The main drawback of global stock market indices may actually be that they imply a somewhat confused allocation by subsegments, rather than allowing a precise and explicit definition of the asset allocation. Sector indices and style indices seem to be appropriate tools that allow investors to gain control over the investment process, while focusing on its most rewarding phase — the asset allocation decision.

This research was commissioned by Af2i (French association of institutional investors), and supported by BNP Paribas Asset Management and UBS.

About Af2i

The aim of the Association française des Investisseurs Institutionnels is to provide a common structure for all economic entities affected by the procedures and techniques used in institutional asset management, regardless of the sector to which they belong (pensions, life assurance and providence schemes, private health insurance and other insurance policies, foundations, specialised institutions, etc.). In particular, its work includes: think tanks, information and support services and the representation of members’ interests. The association has 61 members, with a total of €700bn in managed assets. www.af2i.org