Climate Change Finance: The Big Picture

The transition towards a low-carbon economy will require profound innovations in the way the global financial system manages climate-related risks.

The initiatives to enhance the transparency of climate exposures of banks and asset managers are only the first step in the process of making the financial system resilient to climate risks.

However, financial markets do appear to lack the tools and instruments needed by investors and financial intermediaries to effectively deal with climate risks.

Policymakers should create the conditions to facilitate climate–related financial innovations.

As climate change and global warming are addressed by tougher regulation, new emerging technologies, and shifts in consumer behaviors, global investors are increasingly treating climate risks as a key aspect when pricing financial assets and deciding the allocation of their investment portfolios. So far, the main focus of institutional investors has been on whether policies on carbon emissions will strand the assets of investee fossil-fuel companies. For example, the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund – one of the largest institutional investor globally – announced in November 2017dropping its investments in oil and gas stocks.

However, new estimates are shedding light on the broader indirect impact of climate change on the value of assets held by banks and financial companies. Dietz et al. (2016) show how a leading integrated assessment model can be used to quantify expected impact of climate change on the present market value of global financial assets. They find that the expected “climate value at risk” of global financial assets today is 1.8% along a business-as-usual emissions path, that amounts to US$2.5 trillion - however for the 99th percentile the value estimate is US$24.2 trillion. Importantly, Battiston et al. (2017) finds that while direct exposures to the fossil fuel sector are small (3-12%), the combined exposures to climate-policy relevant sectors are large (40-54%), heterogeneous, and amplified by large indirect exposures via financial counterparties. In other words there is are climate-change-related risks borne by the global financial system that are similar in magnitude to the ones emerged in the financial crisis.

As a sign of regulators’ growing concern about climatic change as a source of risk for the global financial system, the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) created by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) has recently recommended [1] global organizations to enhance their financial disclosures related to the potential effects of climate change.

Still, transparency is only the first step. As carbon risks do appear more pervasive and material for the financial system than previously thought, the compelling issue for investors is how to manage or neutralize such risks once they have been identified and quantified. If investors do not want to retain carbon risk – by covering the potential losses out of the capital invested - what are the possible strategies?

Current approaches to reduce the exposure to climate risks

The quest for tools and approaches that could insulate investment portfolios from environmental risks (and also from other societal risks at large) is not new and over time entire segments of the financial industry have emerged to offer “sustainable”, “green”, or “responsible” financial products. With a focus on carbon risks, the two main approaches appear to be 1) divesting and 2) exercising active ownership.

Divesting or avoiding investments in companies significantly exposed to carbon risks is assumed to result in the substantial “decarbonization” of the investment pool. Some international initiatives – notably, Gofossilfree and the Portfolio Decarbonization Coalition (PDC) - are underway to promote such approach among institutional investors and asset managers. Investors committed to decarbonize their portfolios typically, on the one hand, implement a negative screening in order to identify companies whose operations are exposed to fossil fuels, and, on the other hand, enhance investments in renewable energy (solar, wind, geothermal, hydro and tidal power), enabling technologies (e.g. electric vehicles, smart grids), energy efficiency (e.g. LED lighting, more efficient motors, smart energy management technologies) and products and activities that reduce energy usage (e.g. recycling, insulation, battery storage).

However, as PDC reports “there has been relatively little innovation in terms of the opportunities being presented to them, in particular beyond equities and clean energy”, and “there are relatively few investment managers with a strong track record on decarbonization, and they find that there is an insufficient choice of low-carbon opportunities across asset classes”. Apart from the paucity (relative to the institutional portfolios’ size) of carbon-free assets, the decarbonization strategy presents several implementation shortcomings. Notably the identification of the assets exposed to carbon risks is to a certain extent subjective because it depends on the metrics adopted. For example, the outcome can vary significantly depending on whether the exposure is measured from a Scope 1, 2, or 3 perspectives.

Some financial institutions are trying to curb their exposure to climate risk by exercising their voting rights at shareholder meetings and by engaging directly with the company at Management and Board level. “Active ownership” builds on the assumption that it is the responsibility of a long-term shareholder to question the robustness of financial analyses behind significant new investments made by investee entities. Since fossil fuel companies face the prospect of business decline and must adapt to new circumstances to survive, active ownership by investors may push them to leverage their present strengths towards a low-carbon energy productive system. Since this transition will take time, those entities exposed to carbon risks will need the engagement and support of large long-term investors. By engaging on climate resilience and transition strategies for fossil fuel companies, the investors adopting active ownership can manage the exposure to climate change risks exposure of their portfolio and protect the long-term value of their investments.

Active ownership engagements are conducted either independently or through collaborative initiatives such as CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project) and the major investor climate change networks (the European Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), the Asia Investor Group on Climate Change (AIGCC), the Australia/ New Zealand Investor Group on Climate Change (IGCC) and the Investor Network on Climate Risk (INCR)). Typically, these collaborative engagements aim at encourage companies to disclose their climate change strategies (e.g. the CDP information requests), to set emission reduction targets, and to take action on sector specific issues such as gas flaring in the oil and gas sector. As a recent example of collaborative engagement on climate-related risks, in May 2017 63% of Exxon Mobil shareholders approved a proposal at the company’s annual meeting calling for the world’s largest listed oil producer to improve its disclosure on business risks through global climate change policies.

Rising demand from investors to assess sustainability-related risk and opportunities, has fueled the strong growth of the sustainability information market over last two decades. A range of asset managers use sustainability analyses and ratings in managing their portfolios by comparing quantitative metrics and consolidated scoring for their investment universes.

Sustainability research and analysis assesses the environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance of corporations, and other issuers of securities such as local governments and sovereign States. ESG ratings, rankings and indices aim at measuring the performance and risk of the issuers against ESG criteria. They provide therefore a proxy for the external costs and benefits beyond conventional financial accounting and reporting parameters (Laermann, 2016).

In practice, by establishing an overall score that positions the company on a particular scale, ratings indicate a company's sustainability performance. Investors, depending on their specific selection approach, can use such rating or grade when mapping and managing investment portfolios.

While company engagements and sustainability ratings have helped investors understand and possibly reduce their exposure to environmental risks, the scope and pervasiveness of the problem calls for more decisive action.

The tools needed to decarbonize investments

In a context of carbon priced dynamically, carbon exposure affects the volatility of investment portfolios as well as their long-term returns. A portfolio management strategy that seeks to maximize portfolio returns as its primary goal may be quite different from one that seeks to reduce overall portfolio risk. But whatever the goal, as for other sources of risk, the strategy should be consistently designed, implemented, and evaluated against the primary objective: return impact or risk reduction (Statman, 2005). Setting one objective and then evaluate the results against another could be inconsistent and counterproductive.

The reduction of carbon risks should be a key objective for at least three major categories of financial institutions. First, banks – and especially the “systematically important” ones – need to quantify and manage carbon risks in order to prevent shocks which may potentially not only affect their liquidity and solvency but also pose systemic threats to the financial markets and real economy. Second, the investors who provide financial products and services marketed as “green” or “sustainable” should be able to fully embed effective carbon reduction in what they commit to deliver to clients. Finally, the long-term oriented institutional investors have a particularly strong incentive to proactively manage climate risks. Being the time horizon of investors such as pension funds and sovereign wealth funds long, the likelihood of the materialization of carbon risks affecting their assets is higher. These three categories of investors represent together a large portion of the modern global finance.

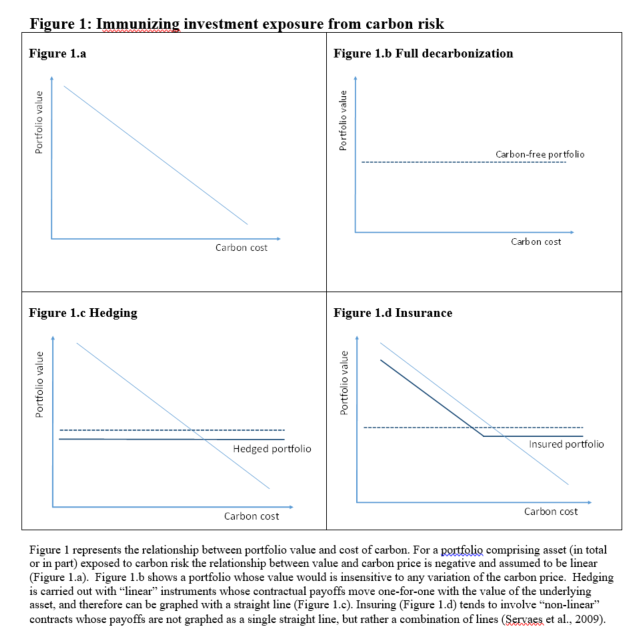

In order to conceptualize the ways those investors can dealt with carbon risks, in Figure 2 we represent the relationship between portfolio value and cost of carbon. We consider that for a investment portfolio comprising asset (in total or in part) exposed to carbon risks the relationship between value and carbon price is negative and we assume that such relationship is linear (Figure 2.a) [2].

In their classical framework, Bodie and Merton (2000) identify three possible approaches to reduce or zero risks. The most intuitive one is risk avoidance, consisting in deliberately avoiding asset risks by excluding those securities and financial instruments that carry such risks. Using the language and the framework introduced in the previous paragraphs, such approach would consist in negative screening and exclusion lists of highly carbon polluting companies. , so that (as shown in Figure 2.b) the portfolio value becomes insensitive to any variation of the carbon price.

The second possible approach is the hedging of the portfolio from the carbon risk. Formally, a risk is hedged when the action taken to reduce portfolio’s exposure to a loss also causes the investor to give up of the possibility of a gain from a favorable configuration of the risk source (Bodie and Merton, 2000). Hedging therefore usually involves “linear” instruments whose contractual payoffs move one-for-one with the value of the underlying asset and so can be graphed with a straight line (Figure 2.c). Those linear contracts tend to be obligations or commitments usually in the form of forward, futures, and swaps (Servaes et al., 2009), but the construction of synthetic positions that deliver the same payoff of a hedging strategy is also possible.

Andersson et al. (2016) presents an alternative strategy to hedge off climate. present an investment strategy that optimizes the composition of a low carbon portfolio index so as to minimize the tracking error with the reference benchmark index. They show that tracking error can be almost eliminated even for a low carbon index that has 50% less carbon footprint. By investing in such an index investors are holding, in effect, a “free option on carbon”: as long as the introduction of significant limits on carbon emissions is postponed they are essentially able to obtain the same returns as on a benchmark index, but the day when carbon emissions are priced the low carbon index will outperform the benchmark (Andersson et al., 2016).

The third relevant risk management strategy is insuring. Insurance eliminates only the adverse outcome, while maintaining potential upside, but an upfront premium is required or ongoing costs. Insurance contracts tend to involve “non-linear” contracts (Servaes et al., 2009) whose payoffs are not graphed as a single straight line, but rather a combination of lines. In the language of the derivatives finance, the insurance scheme represented in Figure 2.d would be the payoff of a put option which gives the investor the right, but not the obligation, to purchase carbon at a fixed price.

As of now, the financial system is lacking the instruments to perform efficiently the hedging and insurance of carbon risks. The space for switching from carbon-risky assets to carbon-free ones is also very limited. Carbon-free securities such as the green bonds are growing steadily and recently created the Luxembourg Stock Exchange launched a Green Exchange entirely devoted to sustainable securities. Still these innovations have to date a very limited scope and may not prove efficient for the implementation of hedging strategies.

On the other hand, carbon negative assets do already exist. Carbon permits in cap and trade systems or the financial contracts related to the REDD and REDD+ schemes are among the most notable examples. However, investors currently have no access to such assets. If the financial system moves - autonomously or because of regulation - towards the implementation of effective risk management policies for such risks, financial innovations - for instance, the securitization of the REDD schemes or the creation of climate and carbon-related derivative securities would be necessary. Moreover, carbon-neutral vehicles and indexes can be designed to make climate risks hedging more effective and accessible to institutional and individual investors. Importantly, carbon risks are not only attached to the securities issued by companies but also to the ones (mostly fixed income) issued by governments. Considering that government bonds are the most relevant asset class held by most institutional investors, the need to insulate such bonds from carbon risks is becoming more and more apparent.

It is difficult to determine ex-ante what products, intermediaries, and financial instruments will serve best the need for the management of climate risks. Assuming a functionalist view of the financial system (Merton and Bodies, 2005), the focus should be more on functions rather than on individual products. The functional perspective views financial innovation as driving the financial system towards the goal of greater economic efficiency, including eco-sustainability.

The innovation will result either in new specialized intermediaries or in new markets serving the need for climate risk protection. Intermediaries will emerge as the solution if climate related products remain low-volume and highly customized. On the contrary, if the products become standardized they will move from intermediaries to markets. In this case, as the volume of traded securities expands, the increased volumes will lower the transaction costs and so make possible further design and launch of new products. Success of these markets and custom products will stimulate further investments in creating additional products and trading markets (Merton and Bodie, 2005), progressively spiraling towards a low transaction costs, dynamically complete eco-sustainable markets.

Unleashing climate-related financial innovation

The latest evidences about the magnitude of climate change risks demand faster and more decisive actions to mitigate the exposure of financial intermediaries and investors – and, as a consequence, of the real economy. As of today, renewables, timber and forests assets, sustainable agriculture investments, and clean-tech ventures can provide only limited hedge for financial institutions. While instruments like the green bonds are gaining momentum, they still channel a minor fraction of the total financial resources needed to be mobilized to achieve the Paris Agreement goals.

There is a clear need to unleash financial engineering to manage climate risks. Policymakers should further promote financial climate-related disclosures for companies and financial intermediaries [3]. Beyond transparency, policymakers should recognize the key role the financial system could play in pricing carbon and in allocating capital towards lower emitting companies. Stable and predictable carbon-pricing regimes would significantly contribute to fostering financial innovation that can help further accelerating the de-carbonization of the global economy even in jurisdictions which are more lenient in implementing climate mitigation actions.

The role of financial markets and financial innovation as a mechanism to enforce climate policy and to accelerate the transition towards a low carbon economy is still overlooked.

References

Battiston, S., Mandel, A., Monasterolo, I., Schütze, F., & Visentin, G. (2017). A climate stress-test of the financial system, Nature Climate Change, 7, 283–288. doi:10.1038/nclimate3255

Dietz, S., Bowen, A., Dixon, C., & Gradwell, P. (2016). Climate value at risk’ of global financial assets. Nature Climate Change, 6, 676–679. doi:10.1038/nclimate2972

Laermann, M. (2016). The Significance of ESG Ratings for Socially Responsible Investment Decisions: An Examination from a Market Perspective, SSRN working paper. Retrieved from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2873126.

Merton, R. and Z. Bodie, (2005). Design of Financial Systems: Towards a Synthesis of Function and Structure. Journal of Investment Management, 3(1), 1–23.

Servaes, H., Tamayo, A. and Tufano, P. (2009). The Theory and Practice of Corporate Risk Management. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 21: 60–78. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6622.2009.00250.x

Footnotes

[1] https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/16_1221_TCFD_Report_...

[2] An analysis that defines the negative relation between (a randomly selected) equity portfolio value and carbon cost is provided by Credit Suisse’s report “Investing in carbon efficient equities: how the race to slow climate change may affect stock performance”, 2015.

[3] Mandatory transparency has been implemented in France and could be enacted at banks in the European Union.