The cost of capital of brown gas

By Noel Amenc, Professor of Finance, EDHEC Business School; Frédéric Blanc-Brude, Director, EDHECinfra; Rebecca Tan, Senior Quantitative Analyst, EDHECinfra; Tim Whittaker, Research Director and Head of Data, EDHECinfra

Would excluding natural gas from the green taxonomy prevent the financing of transition fuels?

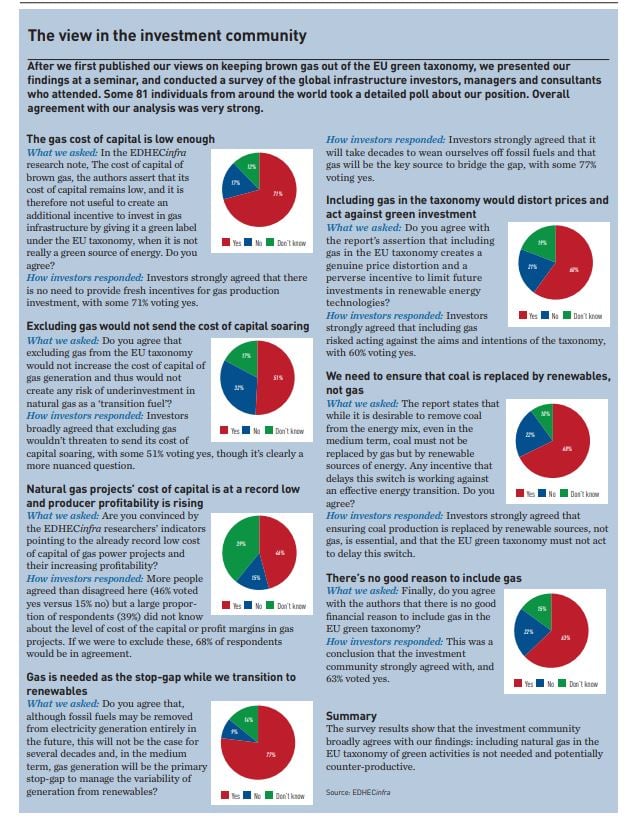

In this article, we consider whether or not natural gas should be included in the EU green taxonomy given the latter’s distorting effect on the cost of capital for energy projects. Excluding gas from the taxonomy would not increase the cost of capital of gas generation and thus would not create any risk of underinvestment in natural gas as a ‘transition fuel’. However, including gas in the green taxonomy creates a genuine price distortion, not to mention perverse incentive to limit future investments in renewable energy technologies. Our conclusion is that there is no good financial reason to include gas in the green taxonomy.

The role of brown gas as a transition fuel

Europe needs gas as a transition fuel to meet its demand for power until renewable energy generation and storage capacity exists on a sufficient scale. Hence, it is arguable that investment in gas projects needs to continue for several decades. While this in no way makes gas a green fuel, there is an argument that investing in gas today supports the transition to a greener energy sector. Consequently, the regulator needs to allow such investments to take place in order to ensure an orderly energy transition.

With its green taxonomy, the EU aims to promote investments in renewable energy by signalling to the market what the desirable types of future investments are today. In turn, this may lower the cost of capital of those investments labelled as green. One may then argue that excluding gas projects from the green taxonomy would penalise their cost of capital, leading to underinvestment, insufficient generation capacity and a disorderly energy transition.

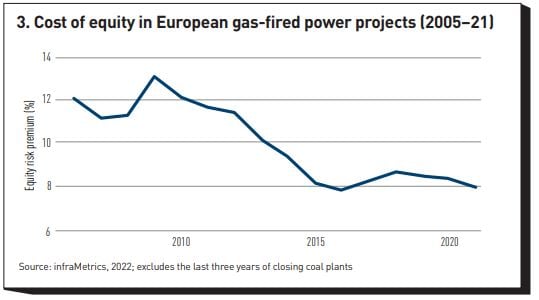

However, this argument is not credible – excluding natural gas from the EU green taxonomy is very unlikely to have a detrimental effect on the cost of capital of gas power projects. Rather, the continuous increase in renewable capacity, combined with the closing of coal generation facilities, has made natural gas increasingly valuable as the generator of last resort to meet Europe’s power demand when the weather fails renewables. As a result, the cost of capital for gas projects, which is already around record lows, is unlikely to increase until renewable energy generation becomes both truly dominant and more predictable.

Moreover, including gas in the green taxonomy has a perverse side effect: it protects (and potentially increases) the option value of natural gas investments that arises from their producer-of-lastresort status, which could even limit capital flows into new renewable energy projects and technologies.

A green taxonomy, a green premium and a brown discount

The role of the green taxonomy is to promote investments in certain sectors by acting as a signpost to the future. The reasoning is that capital markets do not have all the necessary information to make investment choices that fully reflect future risks, notably transition risks. If all the relevant information about the path of future energy transition was available today, markets could allocate capital to the appropriate projects – and a clear green taxonomy acts to fill some of these information gaps.

By creating excess demand for certain investments, the green taxonomy may drive down the cost of capital of the type of investments it promotes – ie, create or increase an existing green price premium. Conversely, it may increase the cost of capital for those investments that it excludes from the green label.

In effect, investors have already started identifying investments as green, especially when it comes to their impact on the global climate, and they have been willing for some time to pay a price premium (receive a lower return) to hold greener stocks (see, for example, Alessi et al [2021]) or unlisted infrastructure equity in sectors such as wind or solar power projects. Existing renewable energy investments have already become expensive. Firstly, they are less exposed to certain risks than conventional energy projects, but also they are in higher demand. Secondly, investors aim to manage climate risks but also have a positive impact and, beyond financial considerations, support the energy transition. As a result, even before the EU introduced its taxonomy, greener infrastructure assets have benefited from a lower cost of capital: as of Q3 2021, the five-year average cost of equity in European wind farms is 50bp lower than in the core infrastructure segment in Europe, and 80bp lower than in the contracted project finance segment, also in Europe (infraMetrics [2021]).

The EU taxonomy may further amplify this positive effect on greener asset prices. A consequence is that it could also limit the supply of capital to less green sectors, especially brown ones that rely on fossil fuels such as coal and gas, and drive up their cost of capital – in effect creating a brown discount. It is in this context that the inclusion of gas in the EU green taxonomy is being considered since it is a useful transition fuel despite the fact that it is by no means a zero-emission fuel. The concern raised is that a brown discount on gas projects in the short term could be counter-productive in achieving the transition to renewable energy.

Thus, a seemingly reasonable argument to include gas in the green taxonomy is the following: the taxonomy will cause capital to flow disproportionately to activities labelled as green by the regulator, and the cost of capital of brown energy sources will soar and lead to underinvestment in natural gas, which is the most important transition fuel for Europe.

Without enough gas-fired generation, the continent would continue to experience a prolonged energy crisis until renewable capacity and storage have had a chance to catch up with the effective demand for power. Brownouts, high energy costs, etc, would become the norm for decades and the energy transition would be very disorderly. Conversely, including gas in the taxonomy ensures that a muchneeded transition fuel enjoys an even playing field in terms of the cost of capital.

Whether or not a green taxonomy truly has this effect on asset prices is an empirical question. It partly depends on which assets are being labelled as green or not. Arguably, the market already prices in a degree of greenness. However, giving a green label to a type of asset that is not green would create a genuine price distortion.

But brown investments are doing well

There is plenty of evidence that, even as renewables have developed, investments in fossil fuels have been doing very well indeed.

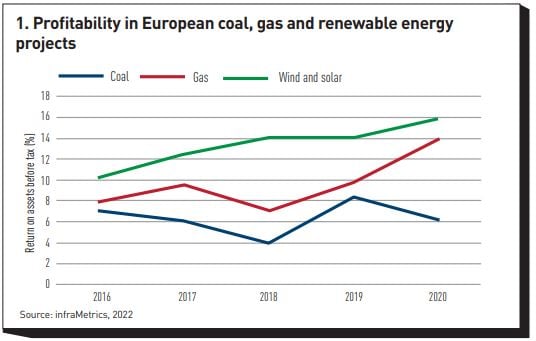

Figure 1 shows the profitability (return on assets) of coal, gas and renewable (wind and solar) projects in Europe over the past five years. While the profitability of renewables in Europe is the highest, gas power projects have enjoyed a significant increase in their profitability, as have coal-fired projects, for reasons we return to below.

EDHECinfra research has shown that profitability is a key determinant of the cost of equity in unlisted infrastructure projects, including energy. Infrastructure companies typically exhibit negative profits during their riskier greenfield phase and, as they develop positive and stable revenues, an increase in profitability is a signal of the successful development and stability of the business.

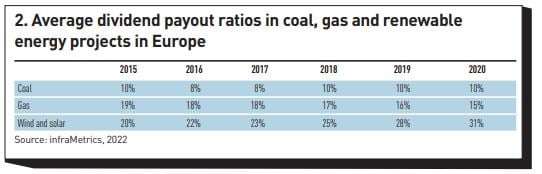

Options to reinvest profits in infrastructure projects are limited, since almost all capital is sunk upfront, and higher profits are a strong predictor of future dividends.

The level of dividend payouts (as a proportion of revenues) for these three sectors is shown in figure 2. Dividends have stayed healthy in the gas and coal power sectors, albeit lower than in wind and solar projects. Coal projects continue to pay 8–10% of their revenues as dividends, gas projects 16–18% and renewables 25–30%. In this light, neither gas nor coal power look like junk. In fact, the costs of capital of gas projects in Europe has been near its record lows in recent years. Figure 3 shows the average equity risk premium of gas-fired power projects in Europe since 2005. After a peak in 2009, the attractiveness of gas power projects led to a steady decrease in their cost of capital. Since 2015, it has hovered around 8% and even fell below that level in 2021.

Gas is now the generator of last resort

While an increasing share of generation is provided by renewables in Europe, this portion is still far from being large enough to meet demand. In the first half of 2021, 40% of electricity generation in the EU was provided by renewable energy sources such wind, solar and hydro (excluding nuclear – EMBER [2021]).

As a result, the reliability of power supply has become more exposed to the vagaries of the weather, as was the case in 2021 with large financial costs incurred by companies and consumers. During that period, Europe experienced an unprecedented ‘wind drought’, with wind speeds down by about 15% (Science|Business [2021]).

To meet power demand, resources further up the ‘electricity merit order’ are required to generate enough electricity.[1] In other words, until enough renewable power and storage can become available, backup generation must be produced by fossil fuel plants (coal and gas). As a result, even coal generation increased significantly in 2021 (Wind Power Monthly [2021]) due to the combined lack of wind with a significant increase in the price of natural gas.[2]

But we know that coal is being phased out with quasi-certainty. The EU reports that the majority of its member states have a policy to phase it out (European Commission [2021]). While policies differ across these states, major economies such as France, Germany and Italy have set expected phase-out dates by 2022, 2035 and 2025, respectively (Beyond Coal [2021]). States that are dependent on coal for electricity generation, specifically Poland, have not yet set any date to end the life of coal power plants but the lack of a plan does not mean that these power plants will not close. The EU’s carbon market is already forcing coal power plants to shift to gas (Politico [2021]).

While fossil fuels may be removed from electricity generation entirely in the future, this will not be the case for several decades. In the medium term, gas generation will be the primary stop-gap to manage the variability of generation from renewables. And as soon as coal is completely out, gas will be the de facto ‘generator of last resort’ to meet European power demand.

From a cost of capital standpoint, the implications are evident: gas power generation is valuable today because in low-wind states of the world, it is the only option to avoid Europe-wide brownouts.

In combination with more variable weather patterns, the current transition to a larger proportion of renewable energy generation increases the volatility of the power generation system and further increases the value of the ‘gas option’. The high value (and profitability) of gas projects confirms that their cost of capital remains low, irrespective of their treatment under the EU taxonomy. Thus, from this point of view, it is not useful to create an additional incentive to invest in gas infrastructure by giving it a green label while it really is not a green source of energy.

The role of investment taxonomies and their potential adverse consequences

While excluding gas generation projects from the green taxonomy would not increase their cost of capital, including them is more likely to have the inverse effect: while the market may already be pricing the greenness of renewables, ‘green gas’ would almost certainly benefit from an even lower cost of capital and become even more valuable to investors.

While this would ensure investment in the designated ‘transition fuel’, it may also slow down the transition away from gas. For instance, with a distorted cost of capital, gas projects will be able to weather a potential carbon tax more easily, making such measures less effective at creating economic incentives to phase out fossil fuels in due course.

As shown above, the ‘gas option’ is already very valuable in a world without enough renewable energy capacity and predictability. ‘Green gas’ thus creates a genuine misallocation of capital since its very existence contradicts the opportunity to invest in better renewable technologies, especially energy storage.

Thus, while excluding gas from the taxonomy would not contribute to a disorderly energy transition, in our view, including it could well slow down this transition. Indeed, the main risk today is not that the energy transition does not take place, but that it takes place too slowly. Any investment incentive created by the regulator must aim to accelerate the evolution of the energy mix towards reduced GHG emissions. While it is desirable to remove coal from the energy mix, even in the medium term, coal must not be replaced by gas but by renewable sources of energy. Any incentive that delays this switch is working against an effective energy transition.

In conclusion, there is no good financial reason to include gas in the EU green taxonomy.

Footnotes

[1] The merit order is the order in which electricity is dispatched. Generally, electricity with the lowest marginal costs of production is dispatched first, followed ever increasingly by electricity with higher marginal costs of production. Renewables with no fuel costs have essentially zero marginal cost. Gas and coal resources have fuel and carbon emissions to take into account before they are dispatched.

[2] The price of gas has increased 250% since January 2021. With the increase in the price of gas, coal-fired electricity became more competitive in the market.

References

- Alessi, L., E. Ossola and R. Panzica (2021) What greenium matters in the stock market? The role of greenhouse gas emissions and environmental disclosures Journal of Financial Stability 54: 100869 Beyond Coal (2021) National coal phase-out announcements in Europe

- EMBER (2021) European electricity review European Commission (2021) State of the energy union 2021: Renewables overtake fossil fuels as the EU’s main power source

- Politico (2021) Poland’s expensive stillborn coal plant

- Science|Business (2021) The great stilling: Can modern technology overcome Germany’s throttled wind energy?

- Wind Power Monthly (2021) Wind-generated electricity in Germany slumps to new low in 2021