Introducing "Flexicure" retirement solutions

By Lionel Martellini, Professor of Finance, EDHEC Business School, Director, EDHEC-Risk Institute and Vincent Milhau, , Research Director, EDHEC-Risk Institute

A major crisis is threatening the sustainability of pension systems across the globe

The first pillar of pension systems, which is made up of public social security benefits and aims at providing a universal core of pension coverage to address basic consumption needs in retirement, is strongly impacted by rising demographic imbalances. Life expectancy at age 65 in OECD countries is expected to grow by 4.2 years for women and 4.6 years for men between 2020 and 2065. As a result, the number of individuals aged 65 and over per 100 individuals aged between 20 and 64, which rose from 13.9 in 1950 to 27.9 in 2015, is expected to grow to 58.6 by 2075.[1]

In parallel, the second pillar of pension systems, which is expected to provide additional replacement income for retirees via public or private occupational pensions, is weakening. In particular, private pension funds have been strongly impacted by the shift in accounting standards towards the valuation of pension liabilities at market rates instead of fixed discount rates, which have resulted in increased volatility for the value of liabilities. The impact of this new constraint has been reinforced by stricter solvency requirements following the 2000–03 pension fund crisis. As a result of these changes in accounting and prudential regulations, a large number of corporations have closed their defined benefit pension schemes to new members and increasingly to further accrual of benefits, so as to reduce the impact of pension liability risk on their balance sheets and income statements. Overall, a massive shift from defined benefit pension schemes to defined contribution pension schemes is taking place across the world, implying a transfer of retirement risks from corporations to individuals.

As an almost universal rule, public and private pension schemes deliver replacement income lower than labour income, and the gap is sometimes severe. According to OECD, an individual with average earnings in the US can expect to receive merely 49.1% of labour income from mandatory pension arrangements when retiring, and the replacement rate falls to 29.0% in the UK. With the need to supplement public and private retirement benefits via voluntary contributions, the so-called third pillar of pension systems, individuals are becoming more and more responsible for their own retirement savings and investment decisions. This global trend poses substantial challenges to individuals, who often lack the expertise required to make such complex financial decisions.

Currently available products fall short of providing a satisfactory answer to the needs of individuals preparing for retirement

In response to these concerns, a number of so-called retirement products have been proposed by insurance companies and asset management firms. Asset management products offer a wide range of investment options, but none of these options really addresses retirement needs because they neither allow investors to secure a given level of replacement income, nor explicitly intend to do so. This is also true for target date funds, even though they are often used as default options by individuals saving for retirement.

In contrast, insurance products, such as annuities and variable annuities, can secure a fixed level of replacement income throughout retirement. However, this security comes at the cost of a severe lack of flexibility, because annuitisation is an almost irreversible decision, unless one is willing to bear the costs of high surrender charges, which can amount to several percentage points of the invested capital. This rigidity is a major shortcoming in the presence of life uncertainties such as marriage and children, changing jobs, health issues, changing locations to lower or higher cost cities or countries, decisions about retirement dates, etc. It also explains why annuities, while offering the security that investment products lack, are in low demand overall.[2]

To sum up, individuals are currently left with an unsatisfactory dilemma between on the one hand insurance products that provide security but lack flexibility, and on the other hand investment products that provide flexibility but no security with respect to the level of future replacement income.

Retirement bond: The safe asset in retirement investment solutions

Fortunately, existing financial engineering techniques can be used to design new forms of “flexicure” investment solutions that can offer individuals both security and flexibility when approaching retirement investment decisions, thus providing a way out of the impasse of a choice between annuities and target date funds. In a recent paper (Martellini, Milhau and Mulvey (2019)), we analyse investment decisions for individuals saving for retirement in the goal-based investing framework, which is the counterpart of the liability-driven investing framework used in institutional money management (see also Deguest et al (2014)), and we argue that costly and quasi-irreversible annuity products are not needed to secure replacement income for a fixed period of time in retirement. To generate income for, say the first 20 years of retirement, a period that roughly corresponds to the life expectancy of a 65-year-old US individual, one can design a dedicated cash flow-matching portfolio made up of liquid fixed-income securities. This ‘goal-hedging portfolio’ is to future retirees what the liability-hedging portfolio is to defined benefit pension funds, and we call it a ‘retirement bond’ because its cash flow schedule matches exactly the needs of retirees. Protection against the risk of living longer than expected can be achieved by purchasing a deferred late life annuity.

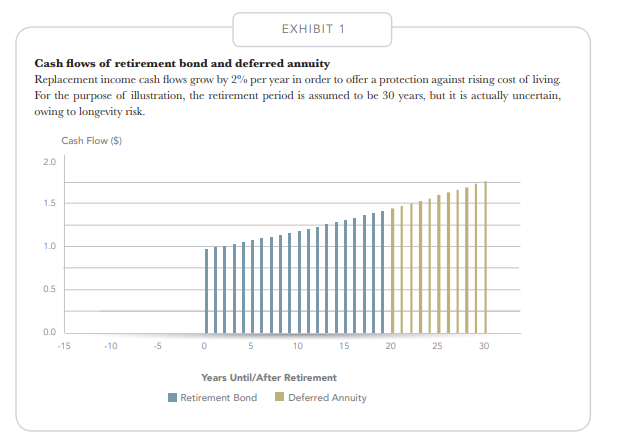

Exhibit 1 shows how an annuity with a cost-of-living-adjustment can be decomposed as the sum of a retirement bond, or retirement bond-replicating portfolio, which covers the first 20 years in retirement, and a deferred late life annuity that takes care of the late retirement period. The blue bars represent the 20 cash flows of the retirement bond and the red ones are the cash flows (in uncertain number) of the deferred annuity that starts right after the retirement bond has matured.

Retirement bonds do not exist as off-the-shelf fixed-income products, but a series of recent articles in the financial and general press has made a case for their issuance by governments and other public or semi-public institutions. Merton and Muralidhar (2017) coin the term ‘SelfIES’ (Standard of Living indexed, Forward-starting, Income-only Securities – see also Muralidhar [2015]; Muralidhar, Ohashi and Shin (2016), Martellini, Merton and Muralidhar (2018), and Kobor and Muralidhar (2018)). These bonds would enjoy the following two main characteristics: (1) payments are deferred to the retirement date, and (2) interest payment and capital amortisation are spread over time in such a way that the annual income paid by the bond is constant or preferably cost of living-adjusted. Their price can easily be obtained by summing future cash flows discounted at market zero-coupon rates, and they can be replicated by standard factormatching techniques like duration hedging and duration-convexity hedging, or by cash flow-matching methods that rely on the stripping of couponpaying bonds and/or interest rate derivatives. These methods are routinely deployed in asset-liability management for the construction of liabilityhedging portfolios.

These dedicated duration-matched bond portfolios are very different from the typical off-the-shelf short duration bond portfolio used by default as the ‘safe’ component in target-date-fund strategies. The latter portfolio is actually unsafe with respect to retirees’ needs because its duration does not match the duration of the targeted cash flow schedule. As a result, it does not properly replicate the performance of the retirement bond, and there is no guarantee that it will deliver the desired cash flows in retirement.

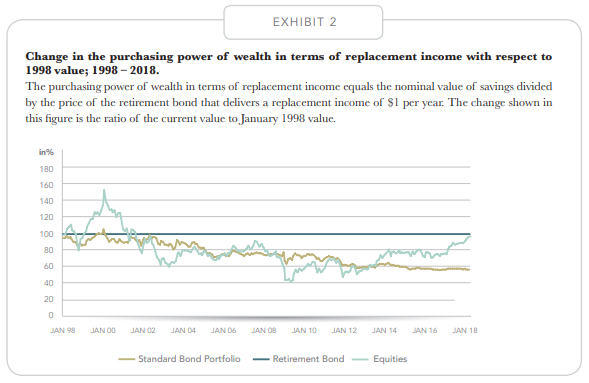

Because the cash flows of the retirement bond are normalised to $1 per year, the purchasing power of savings in terms of replacement income is given by the nominal value of savings divided by the retirement bond price. Given an inception date for accumulation, the funding ratio is defined as the ratio of the current purchasing power to its initial value, so it is equal to the relative performance of wealth with respect to the retirement bond. Exhibit 2 shows the funding ratio for a standard bond portfolio (here taken to be the Barclays US Treasury index with coupons reinvested), for a broad equity portfolio (the market portfolio from Ken French’s website), and for the dedicated retirement bond. The accumulation period ranges from January 1998 to January 2018, and, for simplicity, no cost-of-living adjustment is included here.

By construction, the retirement bond portfolio leads to a funding ratio that stays constant over time, while in this particular sample period the equity and Treasury bond indices failed to keep up relative to the price of the retirement bond. As a result, an investor choosing equities or a standard bond portfolio would have ended 2018 with a lower purchasing power than in 1998. Of course, performance is sample-dependent, and the sample period was marked by an almost continuous decrease in interest rates and three severe bear markets in 2000, 2002 and 2008, through which the funding ratio with equities fell respectively by 35.8%, 36.3% and 53.5%. The retirement bond portfolio benefitted more from the decrease in interest rates than the standard bond index due the longer duration of the former portfolio.

Regardless of the peculiarities of the sample period, a robust insight to be gained from Exhibit 2 is that investing in the standard equity and bond portfolios generates substantial funding ratio volatility. For instance, the standard bond portfolio and the equity index imply volatility levels of respectively 11.46% and 31.30% over the sample period. This confirms that investing in a portfolio that does not take into account investors’ characteristics leaves them with a substantial amount of uncertainty with respect to their replacement income.

Improved forms of target date funds as meaningful retirement solutions

The retirement bond portfolio is intended as a liquid portfolio that delivers stable and predictable replacement income. Each dollar invested in this portfolio allows the individual to secure a fixed number of dollars every year in retirement. On the other hand, and precisely because of this security, investing in the retirement bond portfolio cannot generate upside in terms of replacement income. To increase the achievable level of replacement income without relying only on additional contributions, an investor has to take some risk and invest in assets that are expected to outperform the retirement bond in the long run. A well-diversified equity fund would be a good example of such a "performance-seeking portfolio".

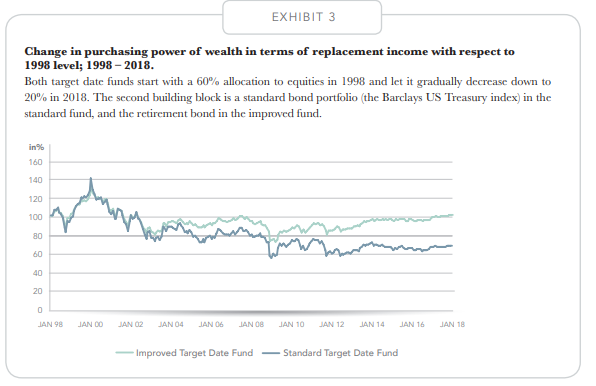

Let us consider as a starting point a target date fund that lets the equity allocation gradually decrease from 60% in 1998 down to 20% in 2018, and construct an “improved” version by replacing the bond portfolio with the retirement bond that starts paying off at the investor’s retirement date. The equity component and the glide path remain unchanged. Unlike the standard target date fund, the improved target date fund explicitly takes into account the nature of the goal (which is to produce replacement income) as well as the investor’s retirement date and decumulation period.

In what follows, we show that the use of the retirement bond in place of the standard bond portfolio leads to substantial improvements in terms of replacement income. To give a first sense of these benefits, Exhibit 3 shows the simulated funding ratios obtained with the standard and improved target date funds.

In this particular sample period, the improved target date fund outperformed its standard counterpart because the retirement bond itself outperformed the bond index. Indeed, the retirement bond benefited more from the decrease in interest rates because of its longer duration. Across a large number of scenarios, the retirement bond portfolio is actually expected to outperform on average the bond index provided there is a positive premium associated with interest rate risk.

Another consequence of the substitution of the standard bond portfolio with the proper goal-hedging portfolio is that the purchasing power of wealth in terms of replacement income displays less variability over time. Numerically, the volatility of annual changes in the funding ratio decreases from 19.09% to 13.54%. The explanation is straightforward because a perfect goal-hedging portfolio has by definition zero tracking error with respect to the retirement bond. Similar results are obtained by replacing the standard bond portfolio with the retirement bond in a balanced fund, which maintains a fixed-mix allocation to the equity and the bond building blocks (see Martellini, Milhau and Mulvey (2019)).

Probabilities of reaching ‘aspirational’ levels of replacement income

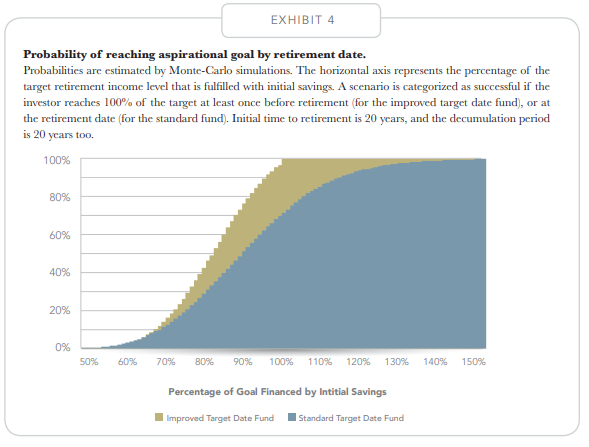

To evaluate the adequacy of an investment solution for an individual, absolute performance is of little relevance. Performance is only useful to the extent that it serves goal achievement, so a better metric is the ex-ante probability of reaching an aspirational goal, defined as a target level of replacement income that the individual was unable to finance at the beginning of accumulation.

Exhibit 4 shows the probabilities of reaching the target income level with both the standard and the improved target date funds introduced above. These probabilities are estimated with a Monte-Carlo model for the returns of the performance-seeking portfolio – modelled as a broad equity index – as well as the return of the standard bond portfolio and of the retirement bond[3]. The horizontal axis represents the percentage of the target income level that can be financed with initial savings. When it is less than 100%, the target income level is a genuine "aspirational" goal because it cannot be financed with initial savings.

For all values of the initial funding ratio, the improved fund generates higher success probabilities measured in terms of probabilities to reach full funding. The benefit of using the improved target date fund is relatively small for severely under-funded individuals, but becomes substantial for initial funding levels starting at 80% and above.

It should be emphasised at this stage that even the improved target fund can experience substantial short-term losses in terms of funding ratio. To address this concern, Martellini, Milhau and Mulvey (2019) introduce a class of risk-controlled portfolio strategies, which adapts standard portfolio insurance techniques to the management of relative risk with respect to the retirement bond, and show that they are effective at capping the size of losses within a given time frame (e.g., one year) to a pre-specified threshold.[4]

Individuals should not have to choose between security and flexibility when approaching retirement investment decisions

In this article, we propose to apply the principles of goal-based investing to the design of a new generation of "flexicure" retirement investment strategies, which aim at offering the best-of-both-worlds between insurance products and asset management products. These strategies can be used to help individuals and households secure minimum levels of replacement income while generating upside exposure through liquid and reversible investment products. In implementation, recent advances in financial engineering and digital technologies make it possible to apply goal-based investing principles to a much broader population of investors than the few traditional clients who can afford customised mandates or private banking services. This environment creates an opportunity to provide genuine investment solutions, as opposed to off-the-shelf products, to individuals preparing for retirement

The pension crisis will not be solved by financial engineering alone. Part of the solution lies in the hands of individuals themselves, who need to start contributing more and earlier so as to more efficiently complement the benefits expected from the first two pillars of pension systems. However, the investment industry does face an ever greater responsibility to provide suitable retirement solutions, especially to individuals who are unfamiliar with basic financial concepts and are therefore not in a position to make educated investment decisions.

In a recent joint initiative, EDHEC-Risk Institute and the department of Operations Research and Financial Engineering (ORFE) at Princeton University have teamed up to design a series of indices called the EDHECPrinceton Retirement Goal-Based Investing index series, which are published on EDHEC-Risk Institute and Princeton ORFE websites (see https://risk. edhec.edu/indices-investment-solutions for more details). It is our hope and ambition that this initiative, as well as related work, can facilitate the introduction of second-generation flexicure target date funds that will be used as part of the solution to the global pension crisis. After all, similar techniques are routinely used in liability-driven investment solutions designed for the benefit of institutional investors, and transporting them to individual money management would be a worthwhile and long-awaited endeavour.

Notes

[1]Figures cited here are from the OECD report Pensions at a Glance 2017.

[2] Other explanations of the "annuity puzzle" are relate to the fact that annuities involve counterparty risk and high level of fees, and also that they do not contribute to bequest objectives.

[3] For the individual who invests in the improved target date fund, probabilities are calculated by implementing a stop-gain mechanism that consists of shifting the entire wealth to the retirement bond whenever the target of replacement income is achievable. This approach is not available for individuals investing in the standard target date funds because the safe retirement bond is by assumption not available to them.

[4] Downside protection is arguably most critical for individuals approaching retirement, as there is then very little time left to recover from a loss that can wipe out a fraction of accumulated retirement savings, and the risk budget can be set to decrease over time. For this reason one may be tempted to introduce a risk buget, or a multiplier, that decrease over time.

References

- Deguest, R., L. Martellini, V. Milhau, A. Suri and H. Wang. (2014). Introducing a Comprehensive Risk Allocation Framework for Goals-Based Wealth Management. EDHEC-Risk Institute publication.

- Giron, K., L. Martellini, V. Milhau, J. Mulvey and A. Suri. (2018). Applying Goal-Based Investing Principles to the Retirement Problem. EDHEC-Risk Institute publication.

- Kobor, A., and A. Muralidhar. (2018). How a New Bond Can Greatly Improve Retirement Security. Journal of Monetary Economics 54(8): 2291–2304.

- Martellini, L., R. Merton and A. Muralidhar. (2018). Pour la création d’ ’obligations retraite’. Le Monde, 7 April.

- Martellini, L., V. Milhau and J. Mulvey. (2019). ‘Flexicure’ Retirement Solutions: A Part of the Answer to the Pension Crisis? Journal of Portfolio Management (forthcoming).

- Merton, R., and A. Muralidhar. (2017). Time for Retirement “Selfies”? Working paper.

- Muralidhar, A. (2015). New Bonds Would Offer a Better Way to Secure DC Plans. Pensions and Investments.

- Muralidhar, A., K. Ohashi and S. H. Shin. (2016). The Most Basic Missing Instrument in Financial Markets: The Case for Forward-Starting Bonds. Journal of Investment Consulting 47(2): 34–47.