Money for Nothing

by Riccardo Rebonato, Professor of Finance, EDHEC-Risk Institute

The market events of March 2020 have ushered in a new era of Quantitative Easing.

It’s not only that the size of the operation in March and April ($2 trillion) has been bigger than the post-Lehmans intervention (a mere $1.3 by the end of 2008), and that the cumulative purchases by the end of 2021 are expected to top $5 trillion. The recent QE interventions have also differed qualitatively: with the purchase of low-credit bonds the Fed has ensured that the corporate credit market would remain open for business; and with the intervention in the 10-year Treasury area it has oiled the wheels of supposedly most liquid market in the world.

The distortions to asset prices (of Treasuries, of course, but of many other securities as well) that this has generated have been discussed at length. One aspect, however, has not received so far the attention it deserves: nobody is looking at inflation. I believe that everybody should be looking at nothing else.

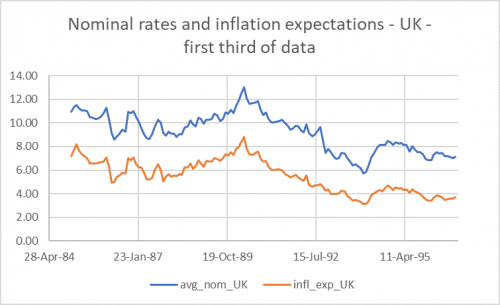

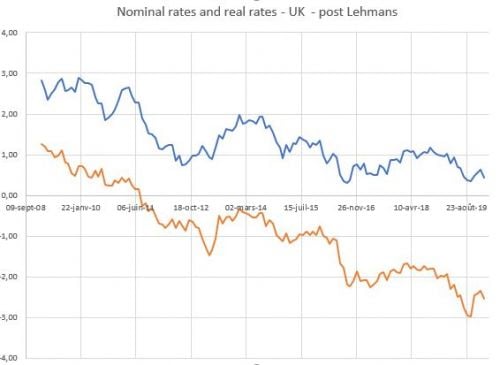

Starting from the first statement: back in the 1980s, changes in expected inflation were fully driving changes in nominal yields (Fig 1 shows nominal yields and inflation expectations and risk premium in the UK from the 1980s to the late 1990s – the correlation is a staggering 97.4%). Fast forward to the post-Lehmans years: as Fig 2 shows, the correlation remains almost as impressive (90.0%), but this time it is with real yields. Inflation now explains nothing. An almost identical picture can be drawn for the US Treasury market, and the German Bunds: the world was obsessed by inflation in the 1970s-1980s, and completely forgot about it in the new century.

Fig 1: The old world: nominal yields and inflation expectations (and inflation risk premia) in the UK from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s.

Fig 2: The new world: nominal and real yields in the UK in the post-Lehman years.

One may say that this makes a lot of sense. The inflation dragon, after all, has been convincingly slain, hasn’t it? It is certainly true that in developed economies inflation is dormant, or even moribund. But what (should) matter for the prices of nominal bonds, is not today’s inflation, but our expectations about future inflation.

And, yes, inflation is non-existent in the midst of the QE-generated money-printing spree, but nobody really understands why: the fact that there are fifteen explanations for the death of inflation suggests to me that at least fourteen, and perhaps all of them, are wrong. The most surprising thing is that inflation remains subdued despite the fact that QE is, effectively, the printing of money – the textbook recipe for creating inflation.

Should we worry? QE is arguably the last monetary game in town, and the demands made of QE have morphed over time: at the very beginning QE was focussed on easing mortgage rates (remember the sub-prime crisis?); then it tried to ease credit conditions in general and stimulate investment . Now, during what economist Richard Koo would call a classic ‘balance sheet recession’, the credit-stimulative effect of lower rates is dubious. However, the latest twist in the QE story goes, the asset bubbles that are being created through asset purchases make asset holders richer, and they should spend more. We all know that richer people spend less of their disposable income that poorer one, but we don’t have at the moment a lot of policy options.

In the current COVID world, the ability of QE to put money in the pockets of asset holders has also given a glimmer of hope to the Treasuries of Western countries, who are faced with the conundrum of what do with the deficits created by the unprecedented, and still open-ended, largesse of the various furlough schemes: instead of raising taxes or cutting benefits, debt can be issued and simultaneously purchased by the central bank via QE. The net effect is to put money in the pocket of Joe Public. And in all of this, somewhat magically, inflation does not appear to materialize.

When we look at the scale and scope of the recent monetary operations, it becomes obvious that they can only work i) for countries where the central bank can print its own money (European peripherals beware), and ii) as long as inflation is absent. If there were a serious uptick in inflation, the whole mechanism would grind to halt first (as further injections of QE stop), and go in reverse then (as central-bank-controlled rates are raised). The financial mayhem that this would generate is not difficult to imagine, and, this time, the central banks would be adding petrol to the fire, not dousing the flames, with their tightening operations.

And here we come to the puzzling bit. Arguably, investors should be reading the inflationary tea leaves with the same bated breath with which one watches a high-wire walking act. Instead, as the figures above show, they seem to be looking at everything but inflation. I do not claim to have any solid understanding of why inflation has so far remained so subdued. But the experience of the 1970s shows that inflation can rise very quickly, very steeply. Long-term lenders, short-term borrowers and investors in general should look at Figures 1 and 2 with attention – and a bit of trepidation.

Part of this article appeared in the news article The inflation dragon is threatening a comeback, published by Treasury Today and included in the Treasury Today newsletter.