The proposed extension of the EU Ecolabel for retail funds needs a rethink

By Frédéric Ducoulombier, CAIA, Director and Head of Climate Policy Advocacy, EDHEC-Risk Climate Impact Institute

The EU Ecolabel in the context of the sustainable finance framework

At end 2016, the European Commission appointed an expert group to develop a roadmap on sustainable finance, requesting advice on how to protect the financial system against environmental risks and steer capital towards sustainable investments. Published at the beginning of 2018, the final report of the “High Level Expert Group” (HLEG) would have a major influence on the architecture and contents of sustainable finance regulation in the bloc and beyond. Some of the priority actions identified by the expert group and that have led to legislation include:

- the development of a sustainability taxonomy starting with climate mitigation;

- the introduction of disclosures on corporates and financial institutions to increase transparency on climate and other sustainability risks;

- the integration of sustainability into the governance of financial institutions;

- the establishment of a green bond standard.

The group’s recommendations also covered:

- retail strategy where the key elements were the integration of sustainability preferences into financial advice, the disclosure of investment sustainability impacts and processes;

- minimum standards for sustainably denominated funds;

- the establishment of a voluntary deep green label.

In view of the environmental emergency, the group recommended that a retail fund label be developed urgently within the framework of the existing label awarded to green products and services (and be later applied to other retail products).[1] While the other components of the retail strategy are now in place, the EU Ecolabel for retail funds is still being discussed, with a sticky issue being the criteria to be applied to determine whether a fund is environmentally sustainable.

In this short contribution, we review the results of a recent study of proposed EU Ecolabel criteria carried out by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA, 2022) and suggest directions to get out of the fix in which the EU Ecolabel extension remains some five years after it was identified as a near-term priority by the HLEG.

Scope and headline results of the ESMA study

Launched more than 30 years ago as the ‘Community Eco-label’, the EU Ecolabel is a world-renowned voluntary label of environmental excellence for goods and services helping consumers identify better options in terms of sustainability. An ISO 14024-compliant Type 1 label, it requires products and services to demonstrate compliance with strict, transparent, science-based criteria attesting to environmental impact reduction along the full lifecycle and to undergo third-party verification.

ESMA Senior Economist Julien Mazzacurati and team have produced very useful work quantifying the proposed extension of the voluntary EU Ecolabel to retail financial products prepared by the European Union's science and knowledge service.

Only 16 out of some 3,000 sustainability-orientated UCITS[2] equity funds (i.e., funds susceptible to report under Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) articles 8 and 9, out of a universe of some 14,000 funds) are estimated to meet the three main quantitative criteria set forth in the latest report of the European Commission Joint Research Centre (JRC, 2021).

Context, methodology, detailed results

The said quantitative criteria are:

- Minimum investments in environmentally sustainable economic activities (based on EU Taxonomy Regulation aligned turnover / capital expenditure) - with a 50% threshold to be achieved at fund level (formula at the bottom of this contribution).

- Environmental exclusions (companies deriving more than 5% of their turnover from environmentally harmful activities);

- Social aspects and corporate governance exclusions (minimum social and governance safeguards, i.e., excluding companies deriving any revenue from socially harmful activities).

For the avoidance of doubt, (2) and (3) are on top and above of the demanding Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) and Minimum Social Safeguard (MSS) criteria required to align an activity and issuer to the EU Taxonomy. (Note that the ESMA analysts assume these EU Taxonomy exclusions away for the analysis thus contributing to overestimation of compliance with criterion 1.)

Assessment of funds against criterion 1 rests on proxy data.

Remember that as per the cartbeforethehorse principle of good regulatory management enshrined in recent European Commission sustainability work – undoubtedly under political pressure to perform in the financial sphere while action in the real economy is postponed – the European regulator has imposed reporting obligations upon institutional investors BEFORE imposing these on corporates issuing the underlying securities. It follows that investors will have to rely on estimates rather than reported data for quite a while – and err on the conservative side as they are advised (precautionary principle) and incentivised (liabilities of all sorts) to. As mentioned in this report, the estimated the share of equity instruments outstanding issued by corporates which will have to disclose Taxonomy-related information under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) stands at only 26% (in value) of EU fund portfolios (ESMA, 2020). This issue will be less of a problem for large EU companies once the NFRD is superseded by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)3]. Taxonomy-related disclosures will remain voluntary and thus unavailable or non-exploitable for most SMEs and non-EU firms.

The ESMA analysts proxy for EU Taxonomy revenues:

- by using a commercial database of estimated green revenues and a granular (undisclosed) mapping to the Taxonomy (why they do not directly use commercially available databases developed to support Taxonomy reporting is unclear but is a second order question) and;

- by filling gaps to the extent possible with the level-4 NACE activity-based approach of Alessi et al. (2021)

They achieve a remarkable coverage score of 98% of fund holdings.

Only 26 sustainability-oriented funds make the cut – the average ‘portfolio greenness’ ratio of sustainability-oriented funds is 11% (close to 20% for Article 9-like funds and close to 10% for Article 8-like funds products). This is on the high end relative to previous published studies, and to the tests this author performed in 2022 using built-for-purpose databases which also addressed DNSH and MSS issues. Note that only 136 funds make the cut even if the ‘portfolio greenness’ threshold is lowered to 30%. Naturally, the future EU Taxonomy expansion beyond climate change mitigation and adaptation activities (to cover the other four environmental objectives) will bring more revenues into scope.

Then the ESMA analysts apply criteria (2) and (3). They candidly observe: “Here again, data availability will be a major challenge for financial product managers.”

Indeed exclusions “cover a wide range of topics spanning multiple sectors.” Here too, proxies will need to be used and (as per the letcommercialdataprovidersridethegravytrain of regulatory-capture prevention enshrined in recent European Commission sustainability work) this requires turning to commercial data providers. However, there is even the risk that institutional investors be required “to collect information directly from the companies, for example with respect to internal social or governance arrangements and policies”. Having every ‘sustainable investment’ manager contact eligible corporates to enquire about these practices comes across as expensive and wasteful (due to duplication) for all the parties involved and eventually for the retail investor.

The ESMA analysts may be forgiven for taking shortcuts through the aforementioned range of topics and for filtering for only four types of controversial activities:

- Fossil fuel (5% of revenues from thermal coal extraction or power generation, oil and gas production or power generation, or 50 % of revenues from oil and gas products and services);

- Pesticides (involvement in the manufacturing of pesticides or distribution or retail sale of pesticides);

- Controversial weapons (a priori reasonable definition to the extent that only involvement in the core system (including components and services) of controversial weapons (not spelled out precisely) is considered);

- Tobacco (manufacturing of tobacco products, supply of tobacco-related products and services or revenues from the distribution or retail sale of tobacco products and services).

Practitioners of core environmental and social exclusions will be aware that the impact of the above will be most material in terms of number of disqualified issuers with respect to involvement fossil fuels (and to a lesser extent nuclear weapons).

After this simplified filtering, 16 out of the 26 funds remain (0.11% of the equity UCITS population and almost 0.53% of the sustainability investing subset).

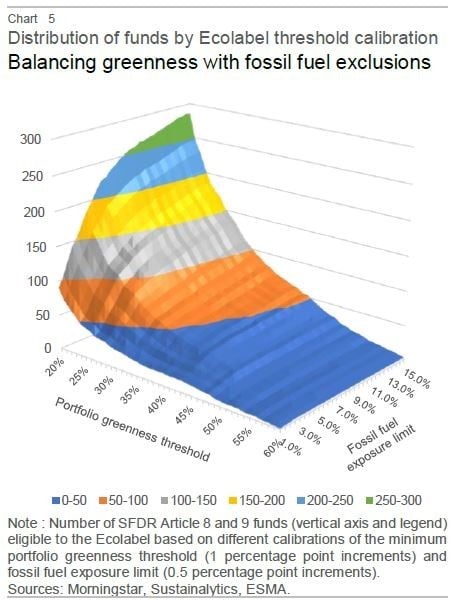

The ESMA analysts conduct a useful sensitivity analysis around thresholds (see their Chart 5, reproduced below) looking at the interaction between the greenness ratio and the fossil fuel exposure limits. A higher portfolio greenness threshold reduces the marginal impact of a tighter fossil fuel exposure limit as should be expected with a dose of industrial specialisation in energy.

© European Securities and Markets Authority

Given the limited supply of 'pure-green' issuers and the state of belated transition towards 'greener' activities, setting high thresholds results in lowered funding extended to 'green' activities.

The authors write: "Under the proposed 50 % greenness threshold and a fossil fuel exposure limit of 5 %, the total value of green assets financed by funds eligible to the Ecolabel would amount to just EUR 3 billion. Under a minimum greenness threshold of 20 % and fossil fuel exposure limit of 15 %, this value increases to EUR 27 billion – at the expense of more money financing fossil fuel activities (EUR 33 billion v EUR 8 billion with a 5 % portfolio limit)."

This is consistent with recent empirical work (Christiansen, 2022) showing that the simplistic energy exclusions rules built in the EU Paris-aligned benchmarks, lead to structural under-funding of transitioning utilities (an obvious nonsense given the electrification needs of the transition). It is also consistent with the green activities undertaken by other energy companies (admittedly the transition promises of oil and gas companies deserve extreme scrutiny and the current involvement of the industry in pushing ‘hopium’ pipe dreams does little to assuage well-placed concerns. It remains the case, however, that thresholds are set too low to reward companies in the fossil fuel ecosystem that choose to break rank and transition in earnest.

In this respect, the ESMA analysts hint that thresholds should be relaxed in combination with strict oversight and materialisation of transition promises: "the Ecolabel criteria 4 and 5 on engagement policy and investor impact can usefully complement quantitative criteria by ensuring that any financing of fossil fuel activities comes with strings attached, pushing investee companies to decarbonise."

Conclusion and recommendations

This ESMA study confirms the reasonable practitioner's concerns about the proposed calibration of the idea of extending the EU Ecolabel to retail investment funds.

As retail investors appear to enjoy a warm glow from choosing the more sustainable investment option, irrespective of how sustainable it is (see Heeb et al., 2023), it is important that sustainable labels, especially those established by the regulator, be designed to be impactful. However, the pool of eligible investment opportunities is simply too narrow to support the high ambitions of the proposal at this stage of the transition (and social and governance filtering further reduce eligible investments).

For the Investment 101 student, the consequences in terms of risk-return profile of eligible funds will be obvious, e.g., concentration and poor factor exposures.

In addition, the procurement of reliable and fit-for-purpose sustainability data is a challenge and will remain so in the medium-term due to poor regulatory scheduling, indicator inflation, lack of definitional clarity, and sometimes wilful ignorance of data limitations (see for example Ducoulombier, 2021, in respect of value chain emissions) or downright metric design flaw (see for example Ducoulombier and Liu, 2021, in respect of the European Commission’s so-called carbon intensity). The benefits of the choices made by the regulator are very clear for commercial data providers but far less so for investors and investee companies. The over-representation of providers of ESG data, analytics and consulting services in technical committees should be a red flag warning the European Commission of the risks of regulatory capture.

It should also be noted that compliance with the additional three proposed criteria requires the demonstration of a clear engagement policy targeting environmental progress along the EU Taxonomy; the existence of approaches and processes to adequately measure, report, and enhance investor impact; and strict information and ongoing non-financial reporting to facilitate compliance assessment. Engagement is understood to be resource-intensive and expensive, and its effectiveness needs to be better measured. As an aside, the preference for engagement over capital allocation and the belief in its effectiveness are decades old and predate any serious investigation. More generally, impact measurement is a relatively new and work-in-progress field for investment managers.

These aspects further contribute to establishing that the Ecolabel proposal needs a rethink if it is to make a meaningful contribution to the transition.

- First and foremost, thresholds could be initially lower to account for the current state of the transition and ramped up over the medium-to-long-term to remain sufficiently challenging as the transition is implemented in the economy. Finance can be used to accelerate the economic transition, but the regulator must first set up the policies and incentives for that transition to begin. The transition cannot be greenwished with the magic wand of finance; the ESMA study demonstrates that there is little evidence of a transition being in progress in the real economy. Channelling capital towards a few ‘deep green’ companies will lead to do little beyond inflating their prices and putting late-stage investor savings at risk).

- Second, the necessity of applying ESG exclusions beyond what is already required under the EU Taxonomy should be challenged.

- Third, activity thresholds and engagement policy should be approached together to allow for a wider range of sustainability investing and impact strategies - capital allocation only strategies would require higher thresholds than strategies focusing on very active engagement and these could be the poles on a spectrum.

- Finally, the data and administrative burden should be kept fit-for-purpose and reasonable and the regulator should make every effort to develop the public and truly open-source provision of sustainability data. The oligopolistic commercial ESG data provision market (now under extra EU ownership) shows impressive levels of profitability and does not require further public subsidies, including of the indirect kind.

Appendix

Fourth Ecolabel technical proposal - computation of portfolio greenness G

G = Σ (PCi * (GTi + GCi)/Ti)

Where:

G = % of total portfolio value invested in environmentally sustainable economic activity (or ‘portfolio greenness’)

i = an individual company in which portfolio equities are held

n = total number of companies in the portfolio

PCi = % Portfolio contribution of company i

GTi = Green Turnover (EUR) of company i of the past (financial) year

GCi = the highest annual Green Capex (EUR) of company i over the past 3 (financial) years

Ti = Turnover (EUR) of company i of the past (financial) year.

Footnotes

[1] The European Commission quickly followed up on the HLEG report with a March 2018 action plan on Financing Sustainable Growth. The document notes that “Labelling schemes can be particularly useful for retail investors who would like to express their investment preferences on sustainable activities. The second of the 10 actions listed refers to “Creating standards and labels for green financial products” and covers green bonds and “the use of the EU Ecolabel framework for certain financial products”.

[2] Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable Securities.

[3] The CSRD entered into force in January 2023. This new directive modernises and strengthens the rules concerning the sustainability (as in social and environmental) information that companies have to report. Relative to the NFRD, a broader set of large companies, as well as listed SMEs and in the reporting scope (c. 50K companies in total). The first companies will have to apply the new rules for the first time in the 2024 financial year, for reports published in 2025. Draft standards prepared by the EFRAG are currently being reviewed by the European Commission.

Bibliography

Alessi, L., Battiston, S., Melo, A. S. and Roncoroni, A. (2019). The EU Sustainability Taxonomy: A Financial Impact Assessment, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Christiansen, E. (2022). Financing the Energy Transition: What is the Role of Fossil Fuels Divestment?, White Paper, Scientific Beta (November).

Ducoulombier, F. (2021). Understanding the Importance of Scope 3 Emissions and the Implications of Data Limitations, The Journal of Impact & ESG Investing, Summer 2021, Vol.1, Issue 4, pp. 63-71.

Ducoulombier, F. (2022). Integrating EU Taxonomy Considerations into the Scientific Beta Climate Impact Consistent Indices, Technical Note, Scientific Beta (March).

Ducoulombier, F. and Liu, V. (2021). Carbon intensity bumps on the way to net zero, The Journal of Impact & ESG Investing, Spring 2021, Vol.1, Issue 3, pp. 59–73.

EC (2018). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Central Bank, the European Economic And Social Committee and the Committee of The Regions – Action Plan: Financing Sustainable Growth, European Commission, COM/2018/097 final (8 March).

ESMA (2020). Final Report – Advice on Article 8 of the Taxonomy Regulation.

ESMA (2022). Investor protection - EU Ecolabel: Calibrating green criteria for retail funds, ESMA Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities Risk Analysis (21 December).

Heeb, F., Kölbel, J. F., Paetzold, F., and Zeisberger, S. (2023). Do Investors Care about Impact?, The Review of Financial Studies, Volume 36, Issue 5, pp. 1737–1787.

JRC (2021). Development of EU Ecolabel criteria for Retail Financial Products - Technical Report 4.0: Draft proposal for the product scope and criteria, Konstantas A., Faraca, G, Dodd, N., Kofoworola, O., Boyano, A. and Wolf, O., Alessi, L., Ossola, E., Joint Research Centre, European Union (March).