Scope for Divergence – The Status of Value Chain Emissions Accounting, Reporting and Estimation and Implications for Investors and Standard Setters

By Frédéric Ducoulombier, CAIA, Director, EDHEC-Risk Climate Impact Institute

This article by Frederic Ducoulombier, Director of EDHEC-Risk Climate, has been originally published in the January/February newsletter of the Institute. To subscribe to this complimentary newsletter, please contact: [email protected].

- The consideration of value chain emissions is crucial as they represent a material source of emissions that companies can address, whether to address impact or transition risks.

- Reporting of these indirect emissions has been voluntary; it remains sparse and is often guided by corporate convenience rather than emissions materiality. While data availability and quality are expected to improve in the medium term, reporting standards are not intended to support cross-company comparisons.

- While data providers model value chain emissions, estimates are divergent and pay insufficient regard to firm specificities to support intra-sector comparisons.

- Investors should treat the integration of value chain considerations into asset selection and reporting cautiously to avoid greenwashing. Value chain emissions may be used to guide overall policy, implement sector allocation, or initiate engagement with companies. Value chain considerations may still be included into asset selection via specific, security-level performance metrics and/or indicators of credible decarbonisation commitments and action.

- Standard setters must avoid requiring, condoning, or encouraging uses of value emissions that are unfit for purpose, notably portfolio construction; they should support disclosure of value chain emissions, targets, and plans, along with their standardisation, including through promotion of sectoral and value chain collaborations.

The number of companies disclosing estimates of greenhouse gas emissions in their value chains is set to increase rapidly in the second half of the decade as mandatory climate reporting ramps up in key jurisdictions and more companies are enticed or pressured by capital providers, business partners, and customers to produce such estimates.

While value chain emissions are widely regarded as critical to understanding an organisation’s climate-related impact and transition risks and opportunities, the perspective of their inclusion in the scope of a US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) climate disclosure rule has led to unprecedented backlash against the integration of sustainability issues into financial management. Acknowledgement of concerns by the chair of the SEC has fuelled speculations that the disclosure of value chain emissions may be curtailed or made voluntary despite very broad investor support. Such an outcome would signify a departure from the strengthening global consensus amongst standard setters and regulators regarding the importance of value chain emissions for investors. Indeed, disclosures on value chain emissions are not only mandated by European Union law but also integrated into the first set of sustainability-related financial disclosure standards endorsed by the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO).

In this piece, we explain why value chain emissions matter; describe the state and future of corporate value chain emissions disclosure; discuss estimation and modelling challenges; and conclude with recommendations for investors and standard setters.

Understanding the Dual Materiality of Value Chain Emissions

Originally published in 2001 by the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol Corporate Standard (“Corporate Standard”) is strongly established as the world’s most widely used GHG accounting and reporting framework.

The Corporate Standard requires that reporting entities first delineate their organisational boundaries, specifying the operations they own or control. The framework then mandates the establishment of operational boundaries, wherein emissions from operations are categorised as either direct or indirect, depending on the consolidation approach (equity share or control) applied to organisational boundaries. Direct emissions, referred to as Scope 1 emissions, emanate from sources owned or controlled by the company. Indirect emissions, on the other hand, are attributable to the entity's activities but arise from sources it does not own or control.

The Corporate Standard further subdivides these into: (i) Scope 2 emissions, stemming from purchased energy (e.g., electricity, steam, heating, or cooling) consumed in equipment or operations owned or controlled by the entity; and (ii) Scope 3 emissions, encompassing other indirect emissions from upstream and downstream activities within the value chain, including the product-use and product end-of-life stages.

Compliance with the Corporate Standard (WRI and WBCSD, 2004) requires reporting entities to measure both Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. The reporting of emissions beyond those from sources “owned or controlled” by the company has been justified on impact grounds by the fact that power generation is the largest source of CO2 emissions globally and the assumption that industrial or commercial entities – which consume more than half of the electricity produced – may exert significant influence on these emissions through energy conservation and efficiency efforts, as well as engagement or replacement of energy suppliers.

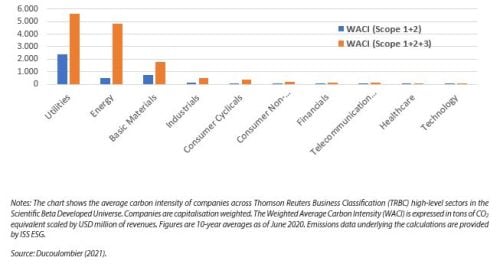

Similar logic has been applied to justify the consideration of Scope 3 emissions, whose accounting and reporting are detailed in the 2011 Corporate Value Chain Standard (WRI and WBCSD, 2011). In most sectors, value chain emissions dwarf direct and purchased energy emissions combined (see Figure 1) and reporting entities often have considerable influence on these emissions through upstream (“cradle-to-gate”) and downstream (post-sale) supply chain decisions, including product design.

Figure 1: Carbon Intensity for Scope 1 and 2 emissions and Total Emissions

Taking stock of indirect emissions has also been justified on business grounds as it allows entities to identify opportunities for cost savings and management of climate-related transition risks, i.e., the risks associated with transitioning to a lower emitting economy, including notably policy/regulatory risks (such as the reduction of fossil fuel subsidies or the introduction of caps on or pricing of GHG emissions); and market and reputation risks).

Limiting analysis to Scope 1 and 2 emissions can lead to incorrect inferences about an entity’s absolute or relative impact and the risks and opportunities it faces. An investor comparing companies that have comparable businesses but different degrees of outsourcing of energy-intensive activities may well draw the wrong conclusions on their environmental footprints or transition risks. Ducoulombier (2021) observes that Apple’s carbon intensity, measured as the ratio of Scope 1 and 2 emissions to revenues, is about 200 times lower than that of rival Samsung Electronics. This does not indicate better efficiency however as, at the time of observation, Apple was fully outsourcing manufacturing whereas Samsung had not yet embarked on large-scale outsourcing. When Scope 3 emissions were included, the difference in carbon intensities fell to a low two-digit percentage.

The consideration of indirect emissions however considerably increases the risk that emissions will be accounted for multiple times. The Scope 2 emissions of an entity are the Scope 1 emissions of energy generating entities. In a portfolio context, aggregating Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions across entities results in double counting when the same emissions are accounted by electricity consumers and their suppliers. Guidance is available to avoid double counting. The problem is greatly compounded with Scope 3 as the same emissions may be accounted multiple times in any value chain, and the problem cannot be neatly unpacked by considering scopes in isolation. How problematic this is depends on how the data are used – from an impact standpoint, it is generally considered that multiple counting indicates the existence of co-responsibility for emissions and/or of multiple levers to tackle them).

This notwithstanding, the consideration of value chain emissions is crucial for reporting entities and investors alike as they represent a material source of emissions to manage from the dual point of view of climate impact and transition risk and opportunities. Recent analysis of disclosures by companies from high-impact sectors found that value chain emissions accounted for three-fourths of their total emissions on average (CDP, 2023).

The State and Future of Scope 3 Emissions Reporting

Voluntary reporting: quantitative strides against deep seated qualitative shortcomings

Mandatory GHG reporting programmes have long been effective in countries responsible for the bulk of global emissions but were focused on direct emissions in heavy industry and the energy sector. The scope of mandatory reporting has expanded over time to listed and large companies and Scope 1 and 2 in multiple jurisdictions and voluntary reporting against the Corporate Standard has also progressed markedly in recent years.

However, value chain emissions reporting up to fiscal year 2023 was voluntary (except for certain large and listed companies in France), and reporting companies lagged in terms of Scope 3 emissions disclosure. Two thirds of the 23,000+ entities contributing data to global environmental disclosure aggregator CDP in 2023 reported direct emissions but only 37% disclosed emissions across all three scopes (CDP, 2024).

Progress in the number of companies voluntarily reporting value chain emissions however has not been paralleled by an improvement in the quality of the data provided. For illustration, a major data provider applying basic plausibility checks rejected nearly three-quarters of the corporate reports it had collected for its 2023 dataset (Singh, Vyawahare and Schrageret, 2023).

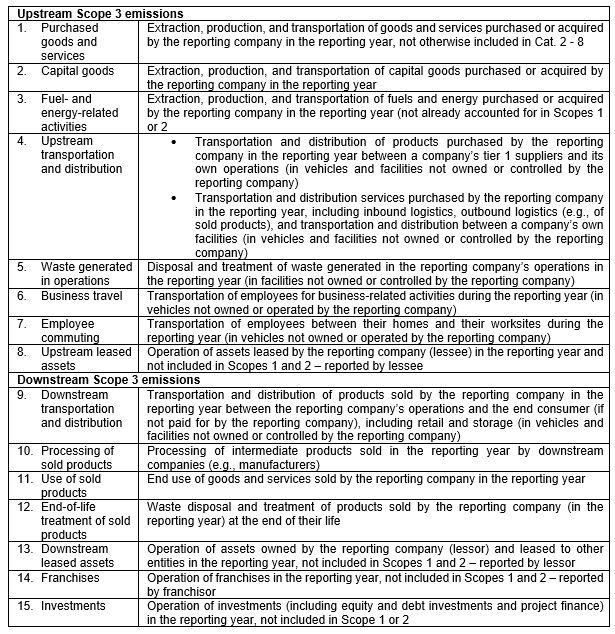

The Corporate Value Chain Standard breaks down Scope 3 emissions into eight upstream and seven downstream categories (see Table 1). Disclosure is on a comply or explain basis and companies can exclude activities or even whole categories of emissions provided this does not compromise the relevance of the reported emissions inventory.

In practice, however, the average reporting company only discloses data for just over a third of the categories, and the majority of reporting entities omit the most material categories.

Table 1: Emissions categories in the GHG Protocol Value Chain Standard

Source: WRI and WBCSD (2013).

Typically, a single category accounts for the majority of emissions, another category has very high significance and it takes at most three categories to capture the bulk of emissions (CDP, 2023). Overall, the most important upstream category is Purchased Goods and Services (Cat. 1) and the most important downstream category is Use of Sold Products (Cat. 11) for non-financial companies. The footprint of the financial sector corresponds to Investments (Cat. 15), which is also the dominant downstream category for listed real estate.

However, value chain emissions disclosure appears to prioritise ‘convenience’ over materiality. As illustration, easy-to-track Business travel (Cat. 6) is the most frequently disclosed category although its contribution to inventories is anecdotal while material categories are under-reported

The reporting of value chain emissions has thus far been sparse, incomplete, and insufficiently focused on material sources. This not only limits the relevance of these data and metrics naively derived from these data for decision-making but also constrains the quality of any estimation or modelling that can be derived from these disclosures.

Mandatory reporting to the rescue?

The number of companies disclosing value chain emissions is set to increase dramatically between now and 2030 as mandatory reporting is now effective in the European Union and was signed into law in California in October 2023.

Other jurisdictions have started to align with the recommendations of the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), whose 2017 version calls for disclosure of value chain emissions “if appropriate” and 2021 update requires it when material. Further impetus has been provided by the June 2023 release of financial disclosures standards by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). The first topical ISSB standard pertain to climate-related disclosures, incorporate TCFD recommendations and require disclosure of material emissions, including within the value chain. In July 2023, the International Organisation of Securities Commissions called on its 130 member jurisdictions to “adopt, apply or otherwise be informed by the ISSB Standards” to promote consistent and comparable disclosures for investors (IOSCO, 2023).

With the introduction of mandated reporting and assurance, the availability and reliability of reported data will improve markedly. However, due to specificities of value chain accounting and reporting, the data will remain irrelevant for certain usages and should be handled with extreme caution by investors.

Indeed, while the Value Chain Standard is intended to promote consistency in accounting and reporting, it affords companies significant leeway in the selection of the inventory methodologies that are appropriate to their circumstances (options are available across the fifteen categories). Likewise, while minimum boundaries are identified for each category, the reporting of certain emissions is flagged as optional.

By way of illustration, companies may use either primary data, i.e., data from specific activities within a company’s value chain, e.g., as provided by suppliers or employees, or secondary data, which may include industry-average-data, financial data, proxy data, and other generic data. While calculations should rely on high quality and highly specific data, such data may be difficult to avail. It is understood that the accuracy and completeness of the inventory will improve over time as more and better data become available and the reporting entity transitions towards more specific calculation methods. Investment in internal resources and processes and long-term engagement of stakeholders across the value chain should improve the quantity, quality, and specificity of data as well as their usage.

The leeway afforded to reporting entities derives from the primary purpose of the Value Chain Standard, which is to help companies track and reduce their emissions over time. This of course may be an issue for parties that approach the data with different objectives and notably cross-corporate comparisons. For such usages, the flexibility of the Value Chain Standard is particularly problematic when it is applied to activities or categories that have material importance. CDP (2017) gives a stark illustration of the problem by comparing reporting of Johnson Controls and United Technologies Corporation (“UTC”), two manufacturers of electrical equipment and engines. While Johnson Controls collects the emissions data from its direct suppliers to compute Scope 3 emissions from the goods and services procured, UTC uses an Economic Input-Output Life Cycle Assessment (EIO-LCA) model to estimate the cradle-to-gate emissions of all products purchased. This results in Scope 3 emissions for Purchased Goods and Services being seven times greater for UTC than for Johnson controls (after rescaling to control for differences in revenues.

Lack of comparability is not limited to the cross section: change of accounting choices over time, in respect of boundaries or methodology inter alia, may generate considerable volatility in the data reported by the same company. While such changes may correspond to progress towards more comprehensive and accurate reporting, they contribute to very high volatility of reported data.

As things stand, the respect afforded currently to reported emissions by certain regulators and standard setters, e.g., the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials puts corporate-reported emissions at the top of its data hierarchy (PCAF, 2022).

Estimation of Value Chain Emissions

The consideration of value chain emissions is key to understanding the climate impact of economic activities and to assessing climate-related transition risk and opportunities. However, corporate disclosures are sparse, incomplete, volatile across time and essentially unfit for cross-sectional comparisons. It is thus natural to explore the potential of emissions modelling to produce more comprehensive, representative, and standardised data to support a wide range of uses.

Corporate-level value chain emissions are available from multiple data providers. Commercial datasets may be comprised of reported data and/or modelled data. Providers including reported emissions in their datasets may choose to redistribute the numbers as sourced; include only those reported figures that pass their quality checks; or adjust reported numbers where needed to increase plausibility or comparability (capping and flooring based on peer group is standard practice). Providers may opt to include only modelled emissions in their datasets and either disregard reported emissions (e.g., by generated estimates from business or financial data) or use these to calibrate and run their estimation models. Differences in data sources and processing (e.g., update cycle, quality controls) will lead to different redistributed values across providers (Nguyen and al, 2023, find identical values for only 68% of reporting firms across two major datasets that use reported values without adjustments; divergence is above 20% for 16% of the data). Differences in estimation approaches, assumptions and model calibration, and input data produce highly divergent values and low correlations across modelled datasets (Busch, Johnson and Piochet, 2022). Studies comparing reported and modelled datasets document low correlations and wide divergence. The degree of divergence is high enough to dramatically alter sorts: comparing a modelled dataset to reported datasets, Nguyen et al. (2023) find that little over one of five observations fall in the same ranking decile and less than a third fall in adjacent deciles (and most of the divergence happens with firms in top or bottom decile by emissions and revenues).

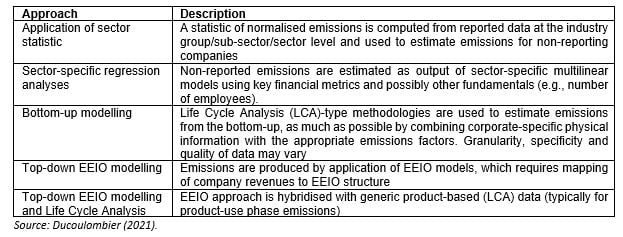

Table 2 gives a high-level view of value emissions modelling approaches. The simplest approaches multiply the non-reporting company’s revenues by the representative carbon intensity (measured as the ratio of emissions to revenues) of a reference group; they ignore differences in business models, and how they may impact total emissions and their breakdown into scopes. Sector-specific multivariate models follow the same logic but allow for consideration of corporate fundamentals beyond revenues. The practicality and the output of such approaches is constrained by the availability, granularity, and quality of reported emissions. Various approaches may be combined to improve estimation by using more specific data when available (including simply extrapolating from past reported data). Multiple models may be run in parallel and combined to produce more stable output. Modelling categories separately should be expected to improve accuracy, but this remains difficult given current limitations of reported data.

Table 2: Approaches Used for the Modelling of Scope 3 Emissions

Environmental Extended Input-Output (EEIO) modelling sidesteps the issue of sparse corporate emissions reporting as it relies on country/industry-level emissions – however, the granularity and precision of EEIO estimates is limited by the availability of corporate revenues breakdown and the definition of the basic modelling unit, and by nature they do not incorporate corporate specificities beyond revenues breakdown.

Life-cycle analysis (LCA) extensions of EEIO models typically rely on representative products per industry and as such cannot incorporate corporate specificities beyond product portfolio composition. Furthermore, certain data provider implementations fail to recognise product differences that have been shown to materially impact value chain emissions. For illustration, up to a recent methodology update, a major data provider was estimating the value chain emissions of automotive manufacturers without considering the shares of electric, conventional, and hybrid vehicles in their outputs.

Bottom-up modelling using LCA principles theoretically has the potential to produce highly corporate-specific emissions, but the dearth of standardised corporate reporting of physical information on outputs and processes makes the approach particularly research intensive, promotes reliance on high-level indicators and sector figures, and introduces subjectivity owing to the need for expert judgment.

Nevertheless, providers that have traditionally relied primarily on regression- or EEIO-based estimation models are increasingly using bottom-up modelling for high-stake sectors for which some physical data can be collected, e.g., the energy and automotive sectors. Bottom-up modelling offers promises but realising its true potential requires meeting the challenges of acquiring reasonably objective, corporate-specific data on both activities and processes, at reasonable cost.

Progress in artificial intelligence seems to pave the way for improving the specificity of emissions estimation at reasonable cost, e.g., by complementing EEIO with machine learning approaches trained to capture the impact on emissions (categories) of differences in business activities, geographies, or financials and fundamentals. This is a relatively new avenue for research and early results do not deliver dramatic changes. Nguyen et al. (2023) find that the use of ‘out of the box’ machine learning models trained on aggregate and category level emissions only produces small improvements in prediction relative to straightforward and traditional approaches (computing emissions from peer-group emissions intensity and revenues, or using a linear model combining revenues, number of employees, and dummy industry indicators).

Altogether, there is insufficient consideration of corporate circumstances, including of business model considerations, in the modelling of value chain emissions. Hence modelled Scope 3 emissions, while preferrable to reported emissions in many ways, are also unfit for the purpose of intra-sector comparisons.

Implications for Investors, and Standard Setters

Investors: ensure value chain data and usages are fit for purpose; explore alternative to value chain emissions

Ensuring fit-for-purpose uses of value chain emissions

Investors need to accept that while the consideration of value chain issues is key from both impact and financial perspectives, the limitations of reported and modelled value chain emissions put severe restrictions on usage.

The quantity and quality of reported data should be expected to make great progress in the second half of this decade; this will pave the way for improvements in the quality and convergence of modelled data. However, in the current state of value chain emissions reporting and modelling, integration of Scope 3 emissions into investment management decisions must proceed with extreme care (as is understood, inter alia, by asset-owner led net-zero coalitions, see Ducoulombier, 2022).

Fiduciary duties (and professional standards) call for taking reasonable steps to:

- diligently assess the quality of data and ensure that it is fit for the intended purpose; and

- transparently disclose the limitations, risks, or uncertainties associated with its use or production.

Fiduciaries should detail the steps taken to mitigate these concerns, where relevant.

Similarly, fiduciaries allocating to strategies that incorporate value chain emissions data should take reasonable steps to assess whether the quality of the data and the way they are used are adapted to the strategy’s objectives and constraints and ensure the strategy is managed in accordance with the investor’s financial and non-financial objectives.

Raw value chain emissions data are typically not fit for the purpose of asset selection. Scope 3 emissions being larger than cumulated Scope 1 and 2 emissions by an order of magnitude in most sectors, basing intra-sector stock-selection decisions on total emissions would drown any corporate-level signals present in reported Scope 1 and 2 emissions in a sea of product- and activity-based Scope 3 noise. Doing so would lead to disregarding the efforts made by companies in the mitigation of their greenhouse gas emissions and must be forcefully opposed (Ducoulombier, 2020 and 2021). Scope 3 emissions data need to be considered separately, if at all.

Metrics and indicators derived from value chain emissions without proper considerations of data limitations should be assumed to have inherited these limitations until established otherwise. Scaling emissions by revenues or enterprise value to produce intensity metrics leaves the problem unaddressed. Portfolio alignment metrics may also be tainted by naïve use of Scope 3 data.

Scope 3 emissions modelling should aim for the highest level of granularity for which sufficient corporate data can be availed or reliably estimated. For more than a decade already, properly modelled value chain emissions have been providing relevant order of magnitude information at the levels of sectors or segments to:

1. Assist in defining priority areas for action;

2. Implement sector allocation;

3. Initiate engagement with companies; and

4. Meet investors’ reporting needs (Raynaud et al. 2015).

When disclosing the emissions of their portfolios and derivative metrics, investors should report the Scope 1 and 2 emissions and metrics linked to their investments separately from their Scope 3 counterparts where information about the latter is required (as mandated by PCAF, 2022). The disclosure of datapoints incorporating the Scope 3 emissions of underlying investments should be accompanied by mentions of data limitations.

Beyond and besides value chain emissions

Value chain considerations still may be included indirectly into portfolio construction and stewardship to incentivise companies to decarbonise throughout their value chains and/or to manage exposure to associated transition risks. This may rely on value chain emissions-related metrics that can support security-level analysis such as:

- financial and/or physical measures of involvement in targeted high impact activities, e.g., fossil fuel involvement, or at the other end of the spectrum, involvement in climate change solutions as identified in sustainable finance taxonomies;

- sector-specific key climate performance indicators, e.g., energy efficiency of products; and

- metrics of upstream and downstream value chain climate-risk exposure, e.g., in the spirit of Hall et al. (2023), etc.

This integration may be pursued through the identification of issuers that take credible steps to address value chain emissions challenges, e.g., produce high-quality inventories, set credible emissions reductions targets and transition action plans, deliver according to targets and plans. Assessment of issuers against such criteria could inform capital allocation and stewardship actions. Such approaches are mandated under voluntary net-zero investment frameworks (Ducoulombier, 2022).

Finally, concerned investors also should include Scope 3 considerations in their policy and issuer engagements, directly and/or through their participation in industry initiatives, to advocate for:

- Scope 3 accounting and reporting to ensure the challenges and opportunities of value-chain decarbonisation are fully appreciated by companies, notably those in high impact sectors;

- Standardisation of Scope 3 accounting at sector level and support of supply chain initiatives to further contribute to data improvement; and

- Adoption of value chain decarbonisation targets by issuers.

Standard setters: avoid abetting greenwashing, support disclosure and standardisation

Standard setters should heed Hippocrates’ advice and first do no harm by ensuring they neither require nor encourage unsuitable usages of value chain emissions. This means ensuring that they:

- avoid mandating portfolio construction on the basis of targets or metrics significantly influenced by the value chain emissions of underlying investments;

- avoid implicitly endorsing the steering of capital allocation by such targets and metrics through mandated disclosures; and

- ensure that voluntary disclosures of such targets and metrics be accompanied by appropriate caveats about data limitations.

Standard setters should be aware of the risks of heightened adverse selection and moral hazard inherent in explicit and implicit endorsement of unsuitable usages of data.

In this regard, the European Commission's decision to steer the construction of its Paris-aligned and Climate Transition Benchmarks by scaled total emissions was particularly detrimental. The choice of metric for what has since become a highly successful investment label contradicts the bloc’s ambitions to redirect capital flows toward the transition to a low-carbon economy and institutionalises illegitimate claims about the impact of these benchmarks. Four years later, with a better understanding of the challenges of value chain reporting and the risks posed by greenwashing, it would be appropriate to realign the Regulation with its stated objectives.

Policy makers committed to the transition should introduce and enforce regulation supporting decarbonisation across the economy. As part of this effort, they should require administrations and firms, starting with large entities, to produce standardised disclosures of emissions and, where relevant, set emissions reductions targets and produce ongoing reports on progress achieved and actions taken to remain on track.

To enhance the effectiveness of these measures, governments should support the production and adoption of sector-specific guidance for emissions accounting, reporting, target setting, and transition plans. Furthermore, they should promote initiatives aimed at fostering cooperation across supply chains and proactively share information and tools to accelerate the adoption of best practices.

References

- Busch, T., M. Johnson and T. Pioch (2022). Corporate carbon performance data: Quo vadis? Journal of Industrial Ecology 26(1): 350–63.

- CDP (2017). CDP Full GHG Emissions Dataset 2016, Technical Annex IV: Scope 3 Overview and Modelling, H. Sawbridge and P. Griffin (lead), CDP Technical Note.

- CDP (2023). Relevance of Scope 3 Categories by Sector, CDP Technical Note.

- CDP (2024). 2023 disclosure data factsheet, CDP, website page accessed on 1 February 2024

- Ducoulombier, F. (2020). A Critical Appraisal of Recent EU Regulatory Developments Pertaining to Climate Indices and Sustainability Disclosures for Passive Investment, White Paper, Scientific Beta, available at: https://www.scientificbeta.com/download/file/critical-appraisal-eu-regul...

- Ducoulombier, F. (2021). Understanding the Importance of Scope 3 Emissions and the Implications of Data Limitations. The Journal of Impact and ESG Investing Summer 2021, 1(4): 63–71, available at: https://eprints.pm-research.com/17511/55152/index.html?84641

- Ducoulombier, F. (2022). Understanding Net-Zero Investment Frameworks and their Implications for Investment Management, Scientific Beta Overview (February), available at: https://www.scientificbeta.com/factor/download/file/understanding-net-ze...

- Hall, G., K. Liu, L. Pomorski and L. Serban (2023). Supply Chain Climate Exposure, Financial Analysts Journal 79(1): 58-76.

- IOSCO (2023). IOSCO endorses the ISSB’s Sustainability-related Financial Disclosures Standards, IOSCO Media Release, 25 July 2023.

- Nguyen, Q., I. Diaz-Rainey, A. Kitto, B.I. McNeil, N.A. Pittman and R. Zhang (2023). Scope 3 emissions: Data quality and machine learning prediction accuracy, PLOS Climate 2(11).

- PCAF (2022). The Global GHG Accounting and Reporting Standard Part A: Financed Emissions. Second Edition, Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials.

- Raynaud, J. (lead), 2015, Carbon Compass, 360 Report, Kepler Chevreux.

- Singh, H., A. Vyawahare, and S. Schrager (2023). Scope 3 Data Quality – Time to Step Up, ISS ESG Blogpost (31 March).

- WRI and WBCSD (2004). The Greenhouse Gas Protocol – A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard – Revised Edition, World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development (March).

- WRI and WBCSD (2011). GHG Protocol Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard, P. Bhatia, C. Cummis, D. Rich, L. Draucker, H. Lahd and A. Brown, World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development.