Taxonomy of Sustainable Investing – An Investment Process Perspective

By Fiona Huang and Lionel Martellini

1. Introduction: Challenges in Sustainable Investing

Following the 2015 Paris Agreement, there has been a steady rise in climate awareness in both the public and private sectors. According to the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), global warming needs to be limited to 1.5 degrees, beyond which climate change will be irreversible, and we only have until 2030 to slash carbon dioxide emissions by 45% from 2010 levels to make any meaningful impact and prevent a much greater climate risk.

In its World Energy Investment Report of 2018, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated that global energy investment totaled 1.8 trillion USD in 2017, with more than 750 billion USD going into the electricity sector and about 715 billion USD being spent on oil and gas.[1] The remainder, some 335 billion USD, was invested in renewables. Not only is the share of renewables the smallest of all energy investments, but it also falls about seven times short of the IPCC’s estimated annual average investment needed of 2.4 trillion USD[2].

One of the major obstacles in attracting funds into sustainable investing is its lack of standardization and clear definitions. The confusion and lack of coherence have hindered the rising interest in this field, and without a common framework, institutional investors will find it difficult to compare and promote relevant funds and financial products. Fortunately, recent discussions have paved the way towards formal recognition of common practices and terminology related to sustainable investing, and useful attempts have been made to establish a clear and detailed classification system, or taxonomy, for sustainable activities – see for example the European Parliament’s Task Force Report on Sustainable Investment Taxonomy (2016).[3].

We strongly believe that creating a common language for all actors in the financial system will be helpful in promoting the private sector’s contribution to long-term sustainable growth. This paper contributes to this objective by providing clarification and a taxonomy from an investment process perspective. Similar to common practice in investment management, it initiates a discussion on the commitment to earning social and environmental returns by drawing on the key distinction between objectives and constraints. Its two main sections then discuss the selection and allocation phases. We hope our paper will provide useful clarification to asset managers and asset owners seeking to promote sustainable investing practices.

2. Mission Determination: Setting Investment Objectives and Constraints

The execution of a sound and meaningful investment process requires investment priorities to be clearly identified before any capital is put to use. When it comes to sustainable investing, properly defining investment priorities means efforts must be made to clarify scope on the one hand, and objectives and constraints on the other.

2.1. Scope: Environment Only versus Environment and Society

In terms of scope, a key distinction exists within sustainable investing between investment strategies with environmental objectives only and more generic investment strategies that also include social objectives. As far as the terminology is concerned, the former approach is often labelled Environmental Investing, Climate Investing or Green Investing, while the latter is most often referred to as Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) or Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Investing.

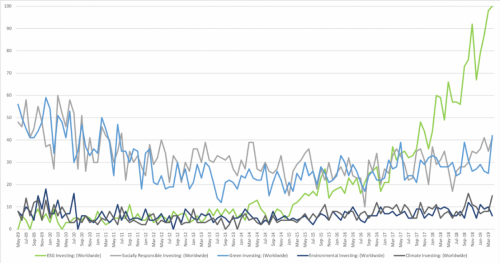

Figure 1 below shows a Google Trend analysis of the five aforementioned terms.

Figure 1: Google Trend Analysis of Common Terms

Usage levels are mainly based on search terms worldwide and limited to web search. Furthermore, usage is rated on a scale from 0 to 100, with a value of 100 indicating peak popularity for the term and a value of 0 indicating a lack of data. While usage levels of “environmental investing” and “climate investing” have remained more or less as they were in 2009, usage of “green investing” and “socially responsible investing” actually declined over the same period. Interestingly, usage of “ESG investing” has grown rapidly over the past decade. Although it is hard to pinpoint the reason for this growth, it could be partly due to the rise in general interest in quantifying ESG factors and academic interest in measuring the impact of these factors on company performance.

2.2. Objectives & Constraints: Performance versus Impact

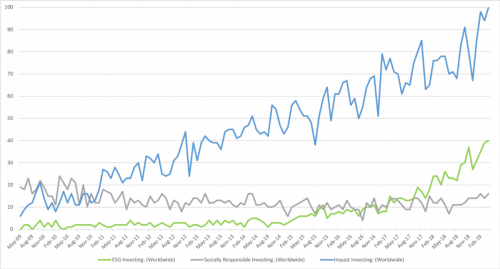

In terms of objectives, although all sustainable investing strategies aim to have a positive environmental and/or social impact, there is a grey scale depending on commitment levels. Borrowing terminology from portfolio construction, we argue that there is a key distinction between strategies that identify performance as the main objective and treat environmental impact as a constraint, and those that instead identify impact as the main objective and treat performance as a constraint. The latter are most often labelled Impact Investing strategies, which can be seen as a subcategory of Sustainable Investing or rather as an extreme case of Sustainable Investing. It is worth noting at this stage that usage of the term “impact investing” has been rising even faster than that of “ESG investing”, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Google Trend Analysis with the term “Impact Investing”

According to the Financial Times Lexicon, impact investment is “generally accepted to describe investing that intentionally seeks measurable social and environmental benefits”. Although this definition is generic enough to sound similar to the broad meaning of any SRI strategy, the key differentiator is that the environmental and/or social returns of impact investing are its main objective. Unlike other investment approaches, the priority of impact investing is its impact. Maintaining a positive financial return is simply a necessary constraint for the fund’s survival, which is how impact investing sustains and distinguishes itself from philanthropy.

Aside from its mission objective and constraint, there is very little limitation on how impact investing can be done. Some financial innovation has aided the growth of impact investing, including financial instruments based on the pay-for-success model, where investors are only paid if certain social or environmental criteria have been satisfied. Direct control is also common in impact investing. Actively managing or intervening in the projects or organizations in which they invest, impact investors often bring shareholder activism to its highest degree, especially in targeted private market investments. As a result, impact investing is usually quite limited in size and is often difficult to upscale.

For sustainable investing strategies with less commitment than impact investing, the fund’s objective is still to achieve a strong financial return, and the constraint is that its environmental and/or social returns have to be above a certain threshold. In this regard, the sustainable investing approach is comparable to the usual investment decision process, where the key questions surround asset selection and allocation. Some impact investing projects could also base investment decisions on these key principles, but many choose to be specialized and adopt a management style similar to private equities.

Lastly, it is also worth noting that the boundary between the two categories is ambiguous. As investment strategies move closer towards impact investing, there will be more emphasis on social and/or environmental returns. As they move closer towards traditional investment management, there is more of a focus on generating financial returns.

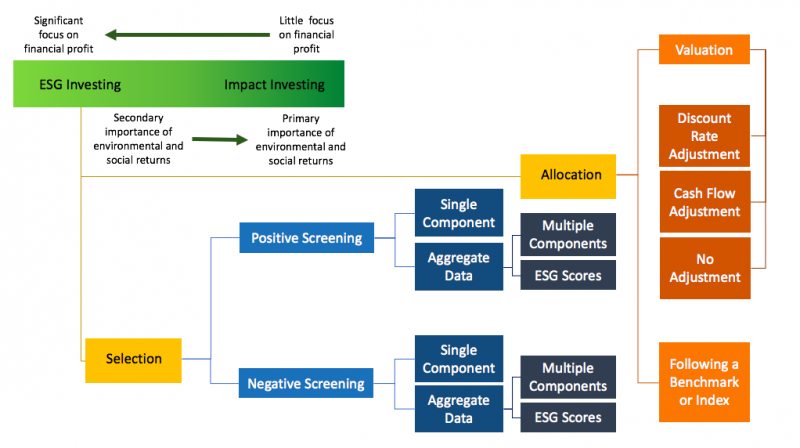

Our discussion is summarized in the upper-left corner of Figure 3, and we elaborate on each section below. While our main focus is on scalable investment strategies with environmental objectives, some of the discussion applies more broadly to ESG strategies. For convenience, in what follows (as well as in the title of the paper) we chose to use the generic term “Sustainable Investing”, which is somewhat neutral and broad and can apply to E factors as well as S and G factors.

Figure 3: Illustrative Chart of Taxonomy from an Investment Process Perspective

Once the investment priorities have been specified in terms of scope, objectives and constraints, the next phases in the investment process are selection and allocation. As illustrated in Figure 3, the classification, or taxonomy, that we propose for sustainable investing reflects the relevance of these two phases in the investment process, which we turn to next.

3.Selection Phase: Screening Scheme

When it comes to the implementation of SRI strategies, a screening-based process is the most commonly used approach for the introduction of ESG constraints in selecting the investment universe. While some asset managers or asset owners choose to perform ESG-related adjustments after selecting assets based on more traditional criteria, including screening as the primary step in SRI is more efficient than only using these factors in the later step, during the asset allocation phase.

Broadly speaking, ESG screening methodologies can be split into two main categories, namely positive and negative screening. The first, sometimes referred to as the best-in-class approach, chooses the assets from an investment universe with the most positive scores on relevant ESG factors. In contrast, negative screening excludes securities from a defined universe, often based on selected characteristics, such as products sold or links to a specific industry. Although the two methods start from two different perspectives, they generally produce relatively similar outcomes.

Whether from a positive or negative screening perspective, asset managers or asset owners can choose between selecting assets based on a single component or aggregate criteria. Commonly used criteria include quantitative factors, such as carbon emissions, but also qualitative criteria, such as a firm’s involvement in a certain industry. Strategies that purposely exclude oil and gas companies in the investment selection phase are a good example of qualitative criteria at work. Aggregate scores, on the other hand, are based on combinations of single factors, either using a customized methodology or some standard methodology implemented by a third party. Such external ESG scores can be used to obtain a proxy for a company’s ESG performance through a standardized system and, as such, can prove useful for asset managers or asset owners with a limited understanding of how to design their own selection criteria based on various sustainability factors.

Although not explicitly expressed in Figure 3, there are subcategories of both positive and negative screening processes. These are all combinations of the previously described criteria designs, but are worth special attention given their popularity amongst asset managers. Ethics-based and value-based exclusion lead to investments determined by aggregate criteria integrated with political, religious or philosophical views. A relatable example could be funds that exclude industries that generate obvious negative externalities in their portfolio, such as gambling, tobacco and alcohol. Another example is funds that exclude companies associated with products or operations involving questionable ethics, such as pornography and animal testing or cruelty.

While some subcategories are based on subjective grounds, there are negative screening strategies based on internationally accepted norms, such as the International Labor Organization standards, UN Global Compact, Universal Declaration of Human Rights and/or other globally recognized norms. This type of screening, known as norm-based screening, provides more objective exclusionary screening criteria, where investments are selected against minimum standards for business practices endorsed by international organizations. At a very basic level, many investment funds use a certain degree of exclusion to prevent financing controversial activities, including the production of weapons or issuers from non-cooperating countries listed by the Financial Action Task Force. But complying with some of these norms not only aligns the fund with the industry’s best practices, it also allows it to receive extra funding and services from various organizations. For example, the International Finance Corporation, a member of the World Bank Group, has a strict policy to only cooperate with financial intermediaries that comply with its Exclusion List.

Like negative screening, positive screening also includes subcategories of investment strategies. Perhaps the most recognized of these is the “best-in-class” approach. While this strategy does not necessarily exclude any specific sector, it selects only companies considered ESG leaders in their respective industries. This allows investors to consider the best practice in each industry and could incentivize companies from all sectors to seek alignment with the competition. Even though it can enable investors to better diversify their ESG portfolio, this method requires a good understanding of all industries in order to define their respective best practices. Alternatively, investors could use a similar approach but select companies based on ESG scores provided by third-party rating services. Both methods could be considered “best-in-class”.

This wide range of screening methods is used by asset managers, but also by index providers. The S&P 500 ESG Index, for example, uses negative screening to exclude companies related to controversial weapons, those with a low UN Global Compact score, and those in the bottom 25% of S&P’s ESG ratings. The weighting of this index is determined by companies’ float-adjusted market capitalization and GICS industry, similar to many other multi-industry stock indices provided by S&P[4]. In this example, the index used ESG factors only at the selection process, but it chose to use more “traditional” index weighting methods for the allocation phase. However, it is also possible to integrate ESG scores into the weighting scheme itself.

4. Allocation Phase: Weighting Scheme

Although many asset managers or asset owners choose to only implement SRI filters in the primary selection phase, a full SRI process should also include SRI factors in the allocation phase. Fortunately, most SRI strategies can be integrated into traditional portfolio construction models, which they enhance through improved risk and performance estimates based on the use of ESG factors. In the case of an ESG assessment, weighting schemes involving an adjustment based on ESG factors can generally be classified as one of two main valuation methods: either an adjustment to projected cash flows or an adjustment to discount rates.

Discount rate adjustments recognize that the cost of capital should be lower for firms with high ESG scores. Indeed, a number of studies have shown that high ESG scores have a positive effect on the firm’s ability to retain a lower cost of debt, due to a perceived lower default risk.[5]. Cash flow adjustments, on the other hand, are based on foreseeable or predictable benefits generated by the ESG factors. Firms with high environmental performances, for example, could sell their carbon emission units to firms with greater needs, earning an extra stream of revenue. Similarly, it is generally agreed among academics that good governance will translate into outperformance in the long run. Firms with good practices are likely to avoid the cost of litigation with other stakeholders, which could also be reflected in future cash flow estimates. Both valuation methods reward firms for their ESG performances, but they reserve the flexibility to adjust the discount rate or expected cash flow.

Moving away from fundamental analyses, weighting schemes used by index providers and passive investment strategies based upon such indices, as alluded to above, can also reflect cross-sectional differences in ESG scores. The STOXX ESG Leaders Index, for example, uses normalized ESG ratings to allocate its stock weightings, in addition to a negative screening selection process similar to that of the S&P 500 ESG Index.[6] The weighting scheme can also combine ESG ratings with more traditional weighting methods. The MSCI ESG Universal Indexes, for example, determine the weight of each security based on three factors: ESG Rating Score, ESG Trend Score and Market Capitalization Weight from the usual MSCI indices. The ESG Trend Score is determined by whether the most recent change in ESG rating was a downgrade, neutral or an upgrade; securities with upgraded ESG have additional bonus weights in the ESG indices. [7]. Another popular index provider, FTSE, also uses a blended approach in its ESG Index Series. However, instead of using an ESG trend adjustment, it applies an additional industry neutral adjustment to match the industry index weightings with corresponding traditional indices.[8]. In both examples, the weighting scheme combines traditional weighting methods with ESG adjustments, and hence the resulting ESG indices still resemble their corresponding traditional indices even after ESG adjustments.

Overall, such weighting adjustments based on ESG factors appear to be purely ad-hoc, and they entirely ignore cross-sectional differences in the risk and return characteristics of the underlying stocks. As a result, it is unclear what assumptions would be required to make them optimal from a risk-return efficiency standpoint. In this context, we believe that further academic research is needed to provide new insights into how optimal weighting schemes could account for firms’ differential exposures with respect to ESG factors in addition to traditional risk factors.

5. Conclusion

This paper is an attempt to establish a taxonomy for sustainable investing strategies, while seeking to outline how sustainable investment processes can be related to common investment practices. There has been a significant increase in ESG awareness amongst corporates and investors since the end of the last century, leading to an increase in the number of responsible investment approaches. More policy makers see sustainable investing as an effective way to achieve sustainable development goals, providing more efficient solutions than direct public intervention and fostering innovation. This trend is likely to continue, but governments and industry bodies need to provide suitable regulatory and legal frameworks so as to attract more capital into environmental and social projects.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.iea.org/newsroom/news/2018/july/global-energy-investment-in-....

[2] https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2018/12/SPM-for-cities.pdf.

[3] http://greenchipfinancial.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Sustainable-Inv....

[4] https://us.spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-bse-100-esg-index-inr.

[5] https://www.db.com/cr/en/docs/Sustainable_Investing_2012.pdf.

[6] https://www.stoxx.com/document/Indices/Common/Indexguide/stoxx_esg_guide....

[7] https://www.msci.com/eqb/methodology/meth_docs/MSCI_ESG_Universal_Indexe....

[8] https://www.ftse.com/products/downloads/ftse-esg-index-series.pdf.