Technological Solutions to Mitigate Transition and Physical Risks – Introducing the infraTech 2050 Database

By Conor Hubert, Sustainability Research Engineer, EDHEC Climate Institute, Rob Arnold, Sustainability Research Director, EDHEC Climate Institute, Nishtha Manocha, Senior Research Engineer, EDHEC Climate Institute

- Infrastructure faces critical risks from climate change, but current tools fall short: Both transition and physical risks threaten the resilience and value of infrastructure assets, yet the high-level or narrow scope of traditional analyses hinders the assessment of localised vulnerabilities and the design of effective mitigation strategies from the asset level up.

- The infraTech 2050 project maps strategies and technologies for emissions mitigation and physical risk resilience: Its database describes these approaches and quantifies their effectiveness through scientific and engineering reviews, providing critical insights to inform asset-level decisions across 101 infrastructure subclasses.

- The InfraTech 2050 database empowers stakeholders across the infrastructure value chain: Developers, operators, contractors, asset owners, managers, and policymakers benefit from fine-grain and actionable risk mitigation insights, supporting decisions that protect assets and promote sustainable and resilient infrastructure.

- Evidence-based insights into strategies, costs, and effectiveness: A deep dive into one of the covered subclasses illustrates how the database evaluates over 70 core risk-reduction strategies, offering actionable guidance for managing transition and physical risks across diverse infrastructure assets.

Climate technology research at the EDHEC Climate Institute is designed to develop knowledge on how assets can leverage technology-driven solutions to achieve decarbonisation and strengthen resilience against physical climate risks. A key component of this initiative, infraTech 2050, focuses on infrastructure. This forward-looking research stream outlines current and promising future strategies for 101 subclasses of infrastructure assets, evaluating their effectiveness for reducing assets’ direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions, as well as their resilience to climate hazards such as floods, heatwaves, storms, and wildfires, up to a 2050 time horizon. Additionally, the project provides insights into the cost implications associated with each of these strategies.

The project features a comprehensive database of strategies and the enabling technologies required for their implementation, alongside scientific assessments of their effectiveness. It also presents academically rigorous research papers and practical case studies to demonstrate how these strategies can be applied in real-world settings.

By offering a comprehensive, systematic, and comparable overview, infraTech 2050 empowers stakeholders to identify the technologies relevant to specific asset types and their comparative performance. This evidence-based approach provides investors, asset managers, and operators with actionable insights to overcome the uncertainties related to tackling infrastructure’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and vulnerabilities to extreme climate hazard events.

In this report, we highlight the significance of the infraTech 2050 database, outline its structure, and present an example of its application by discussing strategies that data centres can use to decarbonise their operations and increase their resilience to extreme heat.

Climate Origins of Infrastructure Risk

Infrastructure companies face two key risks: transition risks from the shift to a low-carbon economy and physical risks from the growing frequency and severity of climate-related hazards.

Transition risks stem from policy and legal changes, technological advancements, market shifts, and reputational challenges, associated with the transition to a low-carbon economy. These risks can manifest as financial impacts, including revenue losses, higher operational expenditures and penalties, impairment of assets and stranding, higher liability, and reduced access to, or higher cost of, capital (TCFD, 2017). Carbon emissions and taxes are commonly used to gauge exposure to these risks. Proactively addressing these challenges through measures such as retrofitting, adopting renewable energy, and improving efficiency can reduce or eliminate transition risks and help maintain business viability.

A frequent challenge for infrastructure is its long-term reliance on fossil fuels. Many assets are built with decades of operational life in mind, which can lock in emissions and make adaptation to a low-carbon economy costly and complex. To mitigate these emissions effectively, it is particularly important to identify the approaches and technologies relevant to various stages of the infrastructure lifecycle and to evaluate their associated costs.

Simultaneously, physical risks threaten the operational integrity of infrastructure. These risks can result in physical and material damage to assets, and/or reduced performance and output, which may in turn, affect asset values and liabilities, decrease revenues, or increase operational and maintenance costs.

Physical risks come in acute and chronic forms. Acute risks refer to single-hazard events, such as, floods, cyclones, heatwaves, or wildfires that cause sudden and significant damage to assets, disrupt operations, and reduce output. Chronic risks emerge from long-term changes in climate patterns, such as rising temperatures, increasing sea levels, or prolonged droughts, gradually impacting operational costs and reducing output and threatening viability. Infrastructure assets face unique challenges due to their extended operational lifespans.

While long-term shifts in climate patterns are being modelled with increasing precision to inform infrastructure planning, challenges remain in accurately modelling the localised impacts of extreme weather events. Transition risks, inherently complex due to their reliance on human decision-making and policy implementation, also present significant challenges for high-resolution modelling. Despite the significance of transition and physical risks, there is a striking lack of information from companies to evaluate whether they are managing them effectively. In our investigation of the sustainability disclosures of approximately 50 major companies with infrastructure assets, the findings were stark:

- Less than one-third of the companies disclosed asset-specific GHG emissions data or provided actionable plans on how they could meet emissions reduction targets.

- Even fewer companies – about one-fifth – assessed the vulnerability of their assets to extreme weather or reported their measures to mitigate physical risks.

Most studies on infrastructure decarbonisation and resilience focus on high-level city, country, or regional analyses or on isolated engineering designs, limiting the ability to conduct comprehensive reviews of vulnerabilities and available mitigation options (Miyamoto, 2019). This lack of granular, transparent information makes it difficult for investors to link actions to outcomes, quantify residual risks, or assess risk management effectiveness. Without reliable data on transition and physical risks, informed decisions about infrastructure sustainability and longevity are challenging.

infraTech 2050 is a crucial first step in addressing transition and physical risks specific to infrastructure assets, reducing knowledge gaps and supporting a low-carbon, climate-resilient future. The database delivers comprehensive insights into strategies for cutting GHG emissions and enhancing resilience to hazards. Tailored for asset owners and investors, it offers actionable guidelines and comparisons across 101 infrastructure subclasses. While valuable for portfolio-level and industry-wide analysis, it complements rather than replaces in-depth, asset-specific assessments like due diligence studies.

Methodology, Structure and Validation Process of the infraTech 2050 Database

Methodology

Approach

The methodology behind the database adopts a top-down approach, drawing on a detailed literature review and case studies to provide a high-level overview of widely applicable strategies for addressing major climate challenges to infrastructure. Unlike a bottom-up approach, which focuses on specific projects and detailed examples, this approach examines general trends and strategic responses across infrastructure sectors.

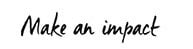

This approach, presented in Figure 1, identifies current and emerging strategies with broad applicability and significant potential impact, pairing them with the enabling technologies required for their deployment, tailored to the needs of specific infrastructure types. This information is complemented by referenced evidence from scientific literature and real-world case studies, providing a robust foundation for assessing and comparing the effectiveness of each strategy in mitigating climate risk.

Classifying Infrastructure

The infraTech 2050 database classifies infrastructure according to the Infrastructure Company Classification Standard (TICCS)[1] , an industry-standard taxonomy that groups infrastructure assets into 8 industrial superclasses, 35 industry classes, and 101 asset-level subclasses. For example:

This provides a detailed framework for describing how risk mitigation strategies serve the unique characteristics of specific asset types.

Strategies and Technologies

The methodology distinguishes between:

- Strategies – Broad actions that achieve specific outcomes, e.g., flood protection, often across a wide range of infrastructure types. The database incorporates current strategies and those likely to be used in the foreseeable future.

- Key Technologies – Specific tools or solutions used to execute measures, e.g., concrete flood barriers.

These levels of granularity enable systematic evaluation of potential impacts and costs. Strategies are chosen based on their materiality, technical viability, and relevance to reducing emissions or enhancing resilience. Technologies are assessed based on literature reviews and expert input.

Materiality

To ensure relevance, the database focuses on strategies that are considered material for each risk and asset class. Strategy materiality is assessed against the following criteria:

- It contributes to significant emissions or physical damage reduction for that asset superclass.

- It applies to a significant number of assets, asset classes or asset subclasses within that superclass.

- The technologies are at a basic level of technical viability and could feasibly be employed by asset owners in the short to medium term. This does not necessarily imply current commercial availability or existing examples of functioning systems.

- It is recognised in industry practice or literature as a key strategy for mitigating transition or physical risks.

Assessing Decarbonisation and Damage Reduction

The methodology quantifies decarbonisation potential by identifying strategies, assessing the effectiveness of associated technologies, mapping them to emission categories, and calculating their impact on emissions.

A similar approach is applied to resilience, focusing on strategies that mitigate physical risks and evaluating their effectiveness and typical protection level.

Assessing Costs

The capital expenditure (CAPEX) associated with each strategy is evaluated using qualitative ratings (low, medium, high), based on estimated cost ranges as a percentage of asset value.

Accounting for Uncertainty

Given the lack of available data in some areas of research, uncertainty ratings are assigned based on:

- The number of available examples.

- Variability in costs or efficacy.

- The maturity of strategies or technologies (e.g., widely deployed versus emerging technologies).

Strategies or technologies with limited real-world deployment or significant variability are assigned high uncertainty ratings.

Assumptions

Key assumptions include:

- Focusing on retrofitting existing assets,

- Treating risks in isolation,

- Assuming consistent costs across classes.

Broader economic or environmental effects are excluded.

Independent oversight

To further strengthen the evaluation and validation processes of the infraTech 2050 project, a dedicated review board is being established, bringing together experts from academia, the private sector, consulting, and government. The board will provide independent oversight of every aspect of the project

As for the database, the review board will contribute to:

- Maintaining its credibility.

- Ensuring that strategies are practical and the knowledge base stays relevant.

- Aligning insights with the latest industry practices, regulatory needs, and academic advancements.

Database Structure

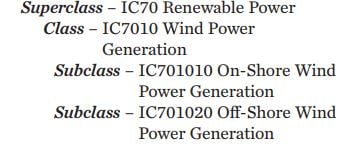

The infraTech 2050 database is a comprehensive tool that combines a structured classification of infrastructure assets with rigorous, evidence-based assessments of decarbonisation and physical risk mitigation strategies. Figure 2 shows the relationship between strategies, and areas of risk.

Each entry is supported by publicly available evidence from academic research, government reports, and technical documentation, providing a robust framework for guiding infrastructure decarbonisation and risk reduction. Each figure is transparently sourced to ensure traceability of the data, thus enabling independent evaluation and, where relevant, challenge or update.

By combining strategy-level information with asset-specific details, the database contains over 1,800 tailored applications. These offer qualitative and quantitative insights, such as technology requirements, effectiveness metrics, and risk protection levels, enabling users to address decarbonisation and resilience challenges effectively.

For transition risks, applicability of strategies to reduce greenhouse gases is considered separately for each of the three different emission scopes defined by the GHG Protocol (WRI and WBCSD, 2004)[2]:

- Scope 1 – direct emissions from sources owned or controlled by the reporting entity.

- Scope 2 – indirect emissions from the generation of purchased electricity steam, heating or cooling that is consumed by the reporting entity.

- Scope 3 – all other indirect emissions in the entity’s value chain, such as emissions from suppliers or customers.

The database presents the effectiveness of a strategy for a specific asset type and scope as a percentage range, representing the potential GHG reduction based on variations in asset characteristics, available technologies, and implementation methods.

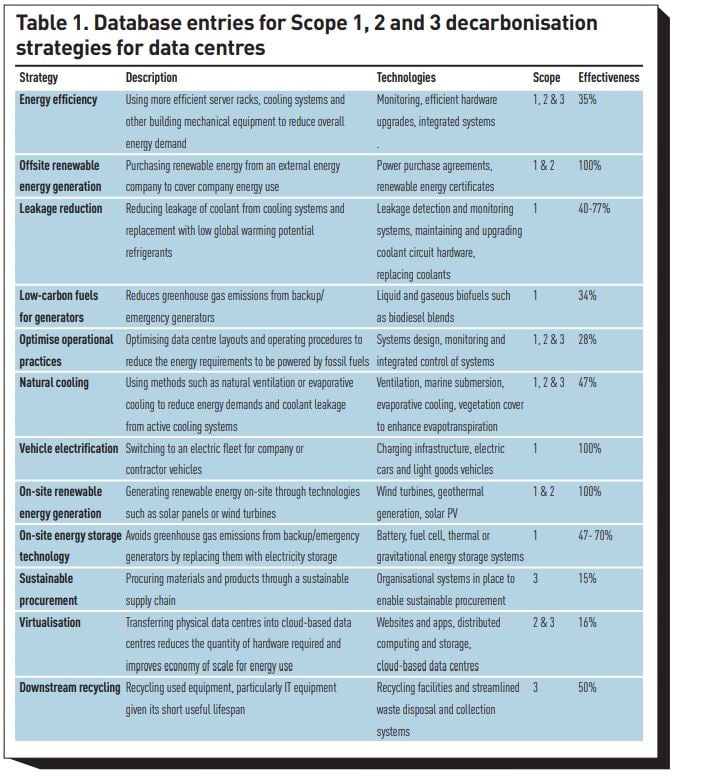

Table 1 presents a sample of the database entries for a data centre (subclass IC502010 in the TICCS taxonomy) for reducing Scope 1, 2 and 3 GHG emissions.

For physical risks, the database provides strategies aimed at mitigating the impact of the following hazards:

- Floods – physical damage from pluvial (rainfall), fluvial (river), or coastal flooding.

- Storms – physical damage from storms and cyclones.

- Extreme heat – operational damage due to high temperatures (including affecting people’s productivity).

- Wildfires – physical damage from wildfires.

These have been chosen as they were the most common climate-related physical risks to assets over the previous two decades (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2020). We assess each strategy’s, effectiveness in reducing physical damage caused by specific hazard events. Effectiveness is quantified based on the severity of the hazard, or by the level of protection offered, such as safeguarding against maximum temperatures of 50°C.

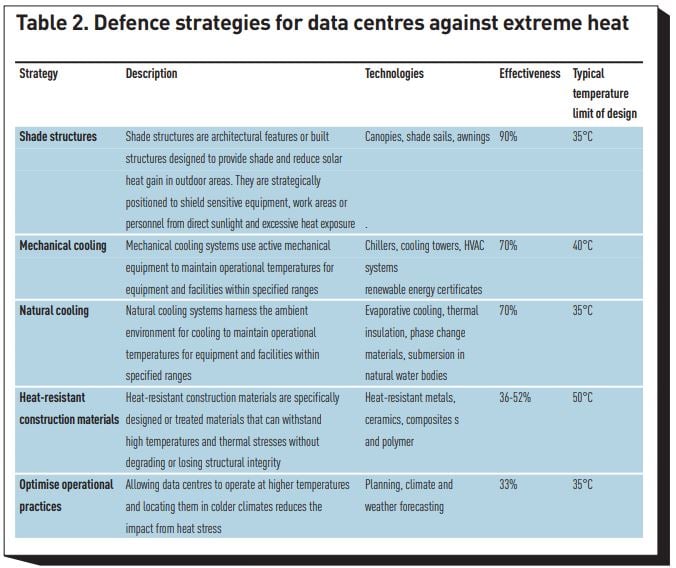

Table 2 presents a sample of the database entries for protection strategies for a data centre against extreme heat.

Using infraTech 2050: Practical Applications for Stakeholders

The infraTech 2050 database addresses the diverse needs of stakeholders who are both involved in and affected by infrastructure development, operation, and climate-related risks. From developers and operators to policymakers, public agencies, asset managers, and the broader value chain, the database empowers decision-makers with actionable insights to manage risks and drive sustainable, resilient infrastructure development. Its applications span multiple levels, including asset-specific, sectoral, geographic, and portfolio-wide analyses, making it a valuable tool for both public and private stakeholders.

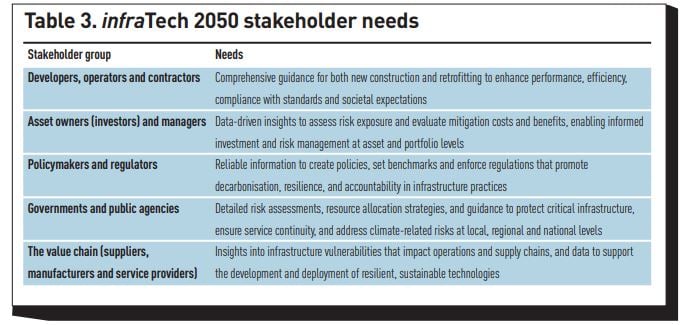

This section explores the key stakeholder groups, their specific needs, and the ways in which infraTech 2050 supports them. Following this, we detail the database’s primary use cases, illustrating its versatility in addressing challenges across infrastructure ecosystems. Understanding the breadth of stakeholders who are involved in or affected by infrastructure development, operation, and risk management—spanning both private investors and public authorities—is critical to appreciating the comprehensive applications of infraTech 2050. Table 3 summarises the key stakeholder groups and their specific needs, highlighting how each interacts with and benefits from the database.

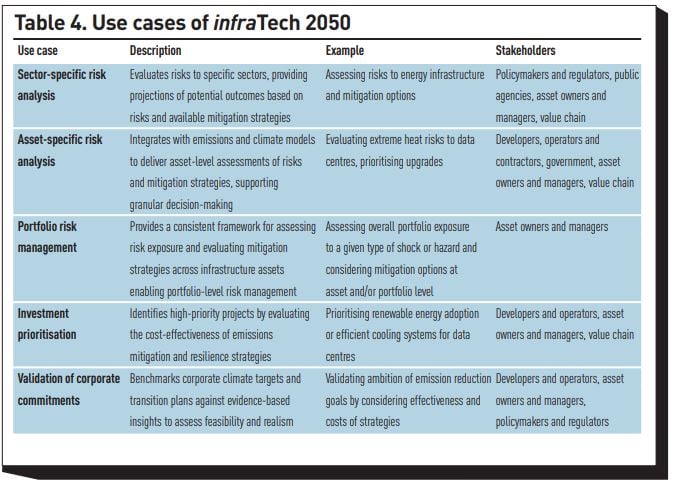

Use cases

The infraTech 2050 database is designed to assist stakeholders across the infrastructure value chain in assessing and addressing climate-related challenges at multiple levels. Table 4 highlights key use cases of the database and the stakeholders who benefit from its actionable insights.

Applying infraTech 2050: Data Centres, Climate Risk, and Resilience

To highlight some of the insights that can be gained from the infraTech 2050 database, we conducted a deep dive into the data centre asset subclass (TICCS subclass IC502010) and will present the strategies that asset owners can use to reduce their transition and physical risks.

Data centres are a pertinent example as they are increasingly critical for the functioning of modern society, have large emissions profiles, and face clear physical risks from climate change. There were about 11,000 data centres globally at end 2023. About half were located in the United States, while the remainder were widely distributed across other countries (Minnix, 2024). This number is expected to increase dramatically in the coming decades.

The large emissions signature of data centres is driven by their energy-intensive operations, including the electricity required for computation and cooling equipment (IEA, 2024). Additional emissions from Scope 3 activities such as the purchase and upgrading of IT equipment leads to ongoing Scope 3 emissions from the supply chain, as well as Scope 1 sources such as vehicle fleets and backup generators.

Data centres are exposed to several physical risks from climate change that can cause damage to assets and have detrimental effects on performance, reducing the asset’s effectiveness and commercial viability. The results for all four major climate-related physical risks are assessed in the database, but for brevity, we discuss only the most material - extreme heat centres (Blair Chalmers, 2020).

Physical Risk

Compared to ageing infrastructure assets in different sectors, data centres are relatively new assets that adhere to higher design and construction standards. This usually incorporates a higher level of physical risk protection, resulting in greater inherent resilience and ability to continue operating during extreme hazard events.

Extreme heat reduces component performance and increases failure risks. For example, extreme heat can cause above ground cables to sag excessively and eventually break. It can also overload data centre cooling systems causing servers to overheat with reduced functionality. In return, servers must be replaced more frequently, which increases GHG emissions.

Data centres provide services to users outside their immediate geographic area and therefore have a degree of flexibility over location that is unavailable for other infrastructure types. Increasingly, data centres are built in colder locations, such as Iceland, to decrease the level of heat risk. On the other hand, high demand and low energy prices resulted in new developments in Texas, with subsequent higher heat risk.

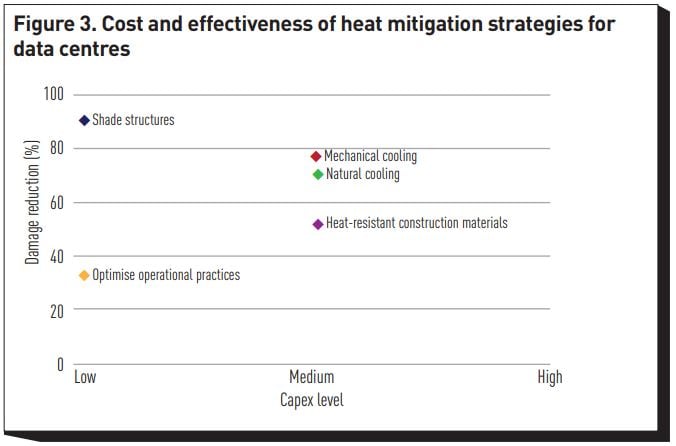

There is a significant interplay between physical and transition risk reduction. For example, traditional methods of managing high temperatures such as mechanical cooling systems, involve high embodied carbon emissions (stemming from their manufacturing, construction, and installation), but also high ongoing electricity usage (approximately 40% of the overall data centre electricity demand (Whiting, 2021)). While these systems effectively reduce physical risk, they increase transition risk by increasing the Scope 2 emissions of the data centre.

Whilst this is a common approach to reducing extreme heat risk, there are several strategies that either produce no additional operational emissions or even reduce emissions, thereby reducing transition and physical risk. These include passive strategies such as natural cooling using environmental air movement, shading structures that block incident radiation, and heat-resistant construction materials that reduce the rate of heat absorption. Additionally, optimising operating practices, such as operational temperature ranges, server room layouts, and loading between different servers, has the dual benefit of reducing heat loading and energy consumption and, therefore, emissions.

Cooling systems and heat-resistant construction materials are cheaper to install during construction and can require substantial building retrofit if done afterwards. However, the increased capital expenditure could potentially be offset by lower operational expenditure.

The costs and effectiveness of the respective heat mitigation strategies are shown in Figure 3.

Transition Risk

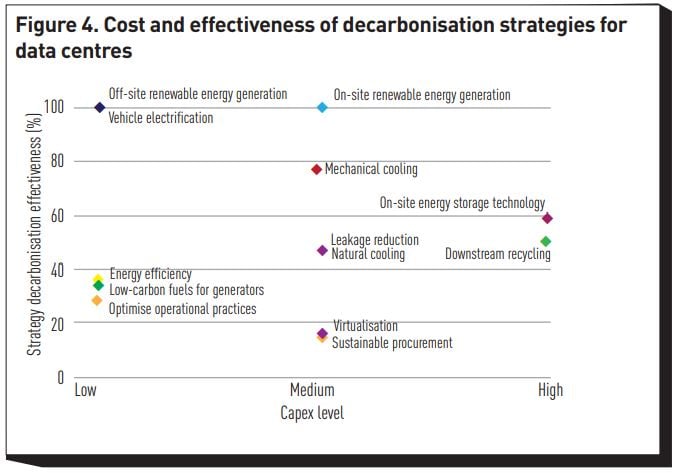

The growth of data centre emissions is influenced by increased construction and usage, driven by rising internet users and traffic (IEA, 2023). In the second half of the last decade, it was largely offset by energy efficiency, renewable energy, and grid decarbonisation, resulting in only a 5% emission increase from 2015 to 2020 (Malmodin et al., 2024). However, emissions are expected to rise in this and the coming decades.

The main sources of emissions for data centres are Scope 2 emissions from electricity usage and Scope 3 emissions from the supply chain, mainly due to the high embodied emissions and short lifecycle of the server equipment. The strategies to tackle these emissions are presented in Table 1 and summarised with preliminary cost insights in Figure 4.

Reducing high-emission electricity demand can be achieved by strategies such as transitioning to renewable energy sources and enhancing energy efficiency. Key measures include upgrading to energy-efficient equipment and optimising operational practices, like improved server room layouts and temperature management to reduce energy usage.

Decarbonising the electricity supply through renewable energy represents the most significant opportunity for impact. However, in many regions, grid capacity constraints limit the availability of renewable energy supply. Using on-site renewable energy generation (e.g., solar panels) in combination with on-site energy storage can overcome this limitation. While this approach may involve higher upfront costs than sourcing renewable energy from third-party providers, it addresses grid limitations, minimises delays in construction timelines, and ensures long-term energy resilience.

Another evolving relationship between data centres and low-carbon energy sources is that of large private sector data centre owners signing power purchase agreements with nuclear energy providers. This includes a mix of strategies such as upgrades to existing (i.e., large) nuclear reactors and the potential restart of shut down plants. Some companies have expressed interest in future data centres being powered by purpose-built small modular reactors (on the potential of challenges of SMRs, refer to IEA (2025).

Additional effort is required to find lower-carbon equipment with longer lifespans that reduce the embodied emissions in data centre supply chains. Sustainable procurement practices, virtualising services and servers, and improving recycling practices can all reduce Scope 3 emissions from these sources but will require collaboration with third parties to achieve.

There is a notable opportunity to align decarbonisation and resilience efforts. The dual objectives of reducing transition and physical risk in data centres can be harmonised with specific strategies that reduce both simultaneously for reasonable costs compared to the potential costs of inaction.

Discussion

Data centres, designed with modern standards, feature advanced physical risk protection, making them more resilient to physical risks than older infrastructure assets. However, as climate risks intensify, even these modern assets face significant challenges, particularly from extreme heat.

Location: A Decisive Factor

The geographic location of data centres plays a pivotal role in their exposure to heat risks. Facilities in colder regions inherently benefit from reduced cooling demands, resulting in lower operational risks and emissions. Conversely, centres in hot regions are often strategically located but face greater heat stress. Balancing location advantages with climate resilience is a key consideration for data centre operators.

Policy and Business Risks

The increasing focus on sustainability brings both regulatory and business risks for data centres. Policymakers are introducing stricter energy efficiency and emissions regulations, pushing operators to adopt greener technologies. Failing to address these risks can result in operational disruptions, reputational damage, and reduced investor confidence. Investors, customers, and regulators alike demand more transparent and robust climate adaptation measures.

A Path Forward: Innovation and Collaboration

To navigate these challenges, data centres must adopt a multi-pronged strategy. Investments in renewable energy, such as on-site renewable energy generation combined with energy storage, can reduce dependency on grid electricity and mitigate construction delays caused by grid capacity constraints. The high energy demand and relative wealth of data centre asset owners provides ample opportunity for funding collaborations necessary to achieve a low-carbon energy supply, both for renewable energy and nuclear power.

Downstream use of waste heat from data centres can reduce the energy use of other assets and provide additional sources of revenue to data centre asset owners, for example using waste heat as an input to a district heating network.

Policymakers also contribute by creating incentives for sustainable cooling systems and renewable energy integration. Pricing mechanisms that reward energy efficiency can accelerate the transition to low-carbon operations.

Data centres are uniquely positioned to lead the way in climate resilience and decarbonisation. By leveraging advanced design standards and adopting innovative cooling and operational practices, the industry can address the twin challenges of extreme heat and emissions. Proactive measures, combined with strong policy advocacy and industry collaboration, will enable data centres to operate sustainably while ensuring long-term reliability. In doing so, they not only mitigate risks but also set a benchmark for other sectors to follow in the transition to a low-carbon future.

Conclusion

Understanding and mitigating climate-related risks is now essential to preserving the value and functionality of infrastructure assets. Reliable, low-carbon infrastructure is critical for reducing GHG emissions and adapting to climate change whilst safeguarding society’s living standards. Yet, systematic and comparable information on climate risks and mitigation strategies for infrastructure assets has hitherto been conspicuously absent.

The infraTech 2050 database offers a structured and evidence-based approach to addressing climate-related risks for infrastructure. Developed by the EDHEC Climate Institute, the database serves as a tool to assist asset owners in identifying ways to reduce risks while enabling comparisons between asset types and strategy impacts. It evaluates over 70 core risk-reduction strategies, linking them to relevant asset types across 101 infrastructure subclasses and assessing their effectiveness. With over 1,800 tailored applications supported by academic research and technical documentation, infraTech 2050 empowers stakeholders to understand the role of infrastructure assets in reducing climate risks in a systematic and actionable way, bridging gaps in knowledge and decision-making.

The database empowers users to address climate risks systematically, overcoming current knowledge gaps, and make informed decisions.

Key applications of infraTech 2050 include:

- Risk Assessment: Evaluating climate-related risks and opportunities at both asset and portfolio levels.

- Strategy Identification and Decision Making: Identifying and prioritising high-benefit, low-risk decarbonisation and resilience projects.

- Stranded Asset Mitigation: Aligning assets with regulatory, market, and societal expectations to minimise the risk of loss of market value, custom or asset stranding.

- Enhanced Decision-Making: Improving planning and ensuring sustainable long-term financial performance by understanding the cost-effectiveness of climate strategies.

infraTech 2050 is envisioned as a dynamic and evolving resource designed to remain relevant and robust in addressing the challenges of climate-related risks for infrastructure. It will be independently reviewed by sector experts to ensure strategies are practical and the knowledge base remains relevant to industry practice.

infraTech 2050 represents a new approach to creating a systematic and comparable knowledge base for climate resilience and decarbonisation opportunities for infrastructure. By aligning expertise and providing actionable insights, it empowers stakeholders to address the dual challenges of decarbonisation and physical risk reduction while supporting the broader transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient future.

Footnotes

[1] TICCS (Scientific Infra, 2022) was purpose-designed for the infrastructure asset class and is thus more informative than investment categories inherited from the private equity and real estate universes.

References

- Blair Chalmers, M. B. (2020). Global Risks for Infrastructure. Technical report, Marsh McLennan.

- International Energy Agency. (2023). Data Centres and Data Transmission Networks. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/energy-system/buildings/data-centres-and-data-transm...

- International Energy Agency. (2024, October 18). What the Data Centre and AI Boom could Mean for the Energy Sector. IEA. Retrieved from https://www.iea.org/commentaries/what-the-data-centre-and-ai-boom-could-...

- International Energy Agency. (2025). The Path to a New Era for Nuclear Energy. IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-path-to-a-new-era-for-nuclear-energy

- Malmodin, J., Lövehagen, N., Bergmark, P., & Lundén, D. (2024). ICT Sector Electricity Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions – 2020 Outcome. Telecommunications Policy, 48(3), 102701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2023.102701

- Minnix, J. (2024), 115 Data Centre Stats You Should Know in 2024. Retrieved on 27 January 2025 from: https://brightlio.com/data-center-stats/, Date Accessed: 27/01/2024.

- Miyamoto, K. (2019). Overview of Engineering Options for Increasing Infrastructure Resilience. Project report. World Bank. Retrieved from https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/fr/474111560527161937/pdf/Final...

- Scientific Infra. (2022). TICCS. Retrieved from https://docs.scientificinfraprivateassets.com/docs/ticcs

- Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). (2017). Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures: Final report. TCFD. Retrieved from https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/10/FINAL-2017-TCFDReport.pdf

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2020). The Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years (2000–2019). United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Retrieved from https://www.preventionweb.net/files/74124_humancostofdisasters20002019re...

- Whiting, A. (2021, August 19). Cooler Data Centres Help Take the Heat off Electric Bills. Horizon Magazine. https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/cooler-...

- World Resources Institute (WRI) & World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). (2004). The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (revised edition). Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Retrieved from https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/ghg-protocol-revis...

- World Resources Institute (WRI) and World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD – 2011). The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: Corporate value chain (Scope 3) accounting and reporting standard. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Retrieved from https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/Corporate-Value-Ch...